Abstract

In an increasingly contested Indo-Pacific region, traditional frameworks of hard and soft power no longer offer sufficient strategic traction. Joseph Nye’s Smart Power served the post–Cold War order. However, today’s gray-zone environment, marked by fragmented sovereignty, systemic fragility, and contested legitimacy, demands a more adaptive and operationally attuned framework. This paper introduces Adaptive Power, a next-generation doctrine of influence built on five interdependent pillars: Timing, Context, Legitimacy, Modularity, and Learning. Unlike Smart Power’s static balance of tools, Adaptive Power emphasizes agility, strategic rhythm, and the contextual fit of influence across domains and timeframes.

It incorporates emerging security principles such as systemic fragility, resilience, enabling influence, and consultative planning, grounded in years of Indo-Pacific field observation and strategic wargaming. The doctrine responds directly to adversaries’ use of Sharp Power—covert, coercive, and manipulative influence—by offering a coherent, legitimacy-driven alternative. Tailored to U.S. and allied competition in the gray zone, Adaptive Power aligns with Department of Defense priorities to campaign in competition, strengthen partner resilience, and evolve deterrence strategy in a fractured security landscape.

Introduction

For much of the modern era, U.S. military power and strategic leadership have played a central role in sustaining global security and deterring large-scale conflict. Today, that role is being tested in new ways, and some go so far as to say that the U.S. is in decline (Adams, 2024). The Indo-Pacific region has become the principal arena for strategic competition, where revisionist powers seek to challenge longstanding norms through coercive influence, incremental encroachments, and hybrid operations short of war. States face fragmented sovereignty, cross-domain threats, contested legitimacy, and a fractured information environment.

In this evolving environment, the effectiveness of U.S. deterrence and influence is shaped less by the scale of its assets and more by how those assets are employed—when, where, and with what degree of legitimacy and responsiveness. Adversaries are operating across legal, informational, economic, and security domains to exploit systemic gaps, shape perceptions, and shift balances of power without triggering direct confrontation. This has revealed critical vulnerabilities in static models of power projection and signaled the need for an updated strategic framework.

This paper introduces Adaptive Power—a doctrine designed to support U.S. strategic objectives in complex, competitive environments. Earlier frameworks, such as Smart Power, offered a corrective to Cold War binaries that emphasized combining hard and soft tools and fused coercion with attraction (Nye 2004, 2010). Yet Smart Power was optimized for a unipolar moment when norms held fast and multilateralism was stable. In contrast, today’s environment is marked by the rise of Sharp Power, which is the use of covert, coercive, and manipulative influence strategies by authoritarian states to exploit openness, sow division, and distort institutional processes (Walker & Ludwig, 2017). These tactics challenge traditional conceptions of deterrence and legitimacy, requiring an approach that is both more agile and more attuned to systemic fragility.

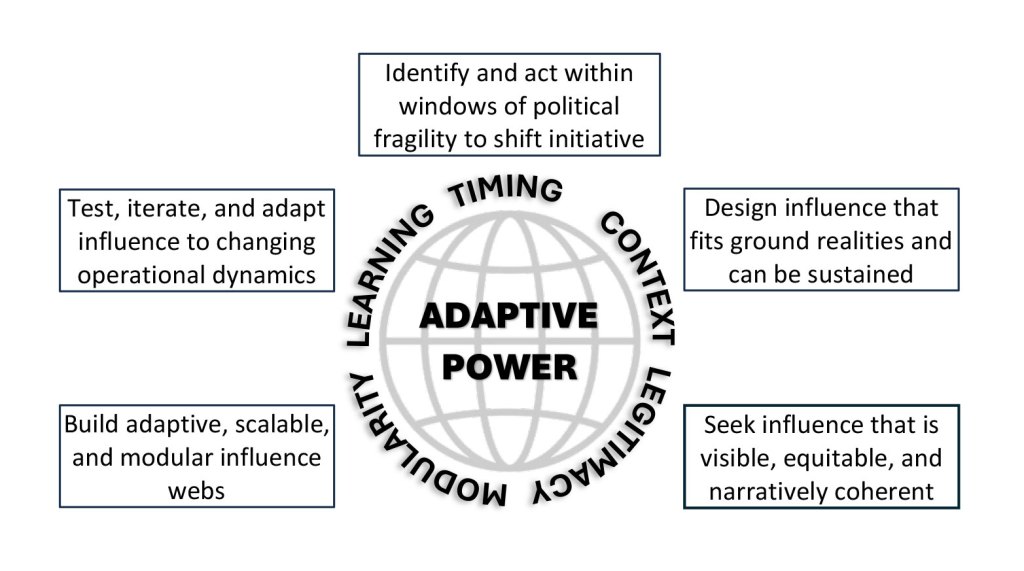

Adaptive Power is more appropriate for the current environment as it emphasizes the operational conditions under which influence becomes effective. It identifies five interdependent pillars: Timing, Context, Legitimacy, Modularity, and Learning. Each is infused with field-tested insights from real-world engagement and strategic wargames on influence operations in fluid and contested spaces, tested by thousands of security professionals throughout the Indo-Pacific.

Drawing from insights on power and irregular warfare by Canyon (2021), regional case studies, and repeated Indo-Pacific wargaming iterations using competitive methodology (Canyon, 2020), the framework matches current Department of Defense priorities of reviving the warrior ethos, restoring trust in the military, and rebuilding to reestablish deterrence, build resilience with allies and partners (DoD, 2022; Olay, 2025). The DKI APCSS wargames (Canyon et al., 2018) offer a structured environment to explore escalation dynamics and assess strategic deterrence by analyzing adversary resolve, defined through stakes, capabilities, and risk tolerance, to provide insights that inform force posture, alliance policy, and extended deterrence planning (Ducharme, 2016). The outcomes of numerous wargames have substantiated the Adaptive Power concept, as explained below.

Adaptive Power offers an approach that is flexible enough to account for shifting realities but grounded enough to inform practical planning and execution. Ultimately, it is “the ability to identify the right approach to achieve a desired outcome, whether it is white, black, or gray” (Canyon, 2021).

What follows is a detailed articulation of each pillar, with implications for how the United States can more effectively project influence, preserve stability, and respond to strategic coercion in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

The Five Pillars of Adaptive Power

Figure 1: Adaptive Power with its five pillars.

- Timing: Acting in Strategic Rhythm

Definition: Strategic influence often hinges not on the volume of action but on when it is applied. In fragile systems, timing determines whether power stabilizes or destabilizes.

Integrated Principle: Systemic fragility. Poor timing in brittle systems (e.g., legitimacy vacuums, post-crisis ambiguity) amplifies missteps and adversary advantages.

Wargame Insight: In more than a dozen Indo-Pacific strategic wargame iterations conducted over several years, the side that succeeded was rarely the one with greater raw power. It was the actor who moved at the right moment, seizing opportunities, anticipating shifts, or forcing decision points.

Timing emerged as the single most decisive variable across every wargame iteration. Players who acted too early often provoked backlash or undermined partner sovereignty; those who acted too late surrendered the initiative to adversaries. Strategic windows, often brief, chaotic, or disguised as minor developments, proved to be inflection points where a small move could cascade into major influence. A GPT model controlled PRC assets and excelled at reading tempo asymmetries as it exploited democratic deliberation cycles, over-reliance on policy consensus, and predictable campaign rhythms. Winning teams internalized that power isn’t just about readiness. It’s about readiness aligned with the moment. Influence becomes effective only when it enters at the speed of political relevance, not the pace of institutional comfort.

DoD Alignment: In military terms, timing is not just about when to fight—it’s about when to engage diplomatically, offer support, or shape perceptions before a conflict starts (Joint Chiefs of Staff 2023a). Adaptive Power aligns with DoD’s shift toward “campaigning in competition”—the idea that we must act continuously to shape the environment, not just surge during a crisis. Timing also reflects what the DoD calls “Phase 0 operations”—activities like exercises, port calls, or information sharing that build influence before conflict arises. When done well, this proactive engagement closes the window for adversaries like China to exploit instability.

Case Study 1: The Solomon Islands Security Pact (Herr, 2022)

Context: In early 2022, civil unrest erupted in Honiara, Solomon Islands. Amid institutional fragility, the PRC rapidly advanced a bilateral security agreement before the U.S. or Australia could act. The issue wasn’t capacity; it was timing failure in a fragile moment.

Challenge: The U.S. and Australia were diplomatically present but failed to act during the window of maximum political ambiguity and public discontent.

Action: The PRC moved decisively, signing a security deal that opened the door for Chinese police and potentially military presence. The U.S. response came weeks too late, with offers of increased engagement falling flat.

Doctrinal Insight: This episode exemplifies timing as a center of gravity. Influence was lost not for lack of tools or presence, but because both the U.S. and Australia failed to recognize a threat and act within the fragility-tempo window.

- Context: Power Must Fit the Terrain

Definition: Influence must align with local histories, governance structures, legal frameworks, and cultural norms. Abstract power applied without contextual fit produces backlash or irrelevance.

Integrated Principle: Consultation. Context must be read, not assumed—through legal review, civic dialogue, and trust-building at multiple levels.

Wargame Insight: In the wargame environment, strategic missteps consistently occurred when players projected influence without accounting for the local sociopolitical terrain. The most effective teams approached regional actors not as passive recipients but as co-authors of the strategic environment. This echoed real-world dynamics, where actors like the PRC embed influence in cultural familiarity and legal ambiguity—often outpacing U.S. efforts rooted in institutional templates. A GPT model, simulating PRC logic, consistently exploited moments where players failed to read cultural nuance or political subtext. Success came not from force projection but from strategic empathy—anticipating how a nation sees itself and tailoring moves accordingly. Contextual intelligence—legal, cultural, historical—is not a supplement to influence operations; it is the entry ticket.

DoD Alignment: Understanding context is at the heart of mission command and joint planning (Joint Chiefs of Staff 2023b). These doctrines emphasize that local commanders, diplomats, and partners must have the flexibility to tailor action to their specific environment—not just follow a one-size-fits-all plan from Washington. Adaptive Power reinforces what DoD planning guidance already demands: deep situational awareness, legal and political sensitivity, and alignment with partner priorities. In Indo-Pacific operations, this means knowing how a local community views U.S. presence, how laws shape what can be done, and how history affects perception. Ignoring these factors can turn helpful actions into sources of mistrust.

Case Study 2: U.S.–Papua New Guinea Defense Cooperation Agreement (DOS 2023)

Context: PNG has a history of legal sensitivity regarding sovereignty, and especially foreign troops and resource control. The 2023 U.S.–Papua New Guinea Defense Cooperation Agreement succeeded through legal and political consultations with domestic institutions, ensuring the agreement did not violate PNG sovereignty or stoke backlash.

Challenge: Early U.S. defense discussions raised internal political concerns and initial signs of public outrage on social media. Without transparency, the deal risked public backlash or constitutional challenge.

Action: U.S. negotiators engaged PNG constitutional lawyers, held civic briefings, and allowed significant local legal shaping of the agreement. The final DCA passed smoothly.

Doctrinal Insight: Influence landed because it was shaped by deep contextual understanding, enabled by consultative processes, and aligned with local constitutional logic. Influence strategies in a contested environment benefit from considering geography, regional history, and narrative framing (Medcalf, 2020). This is the essence of context-fit influence.

- Legitimacy: The Decisive Battlespace

Definition: Legitimacy—perceived fairness, reciprocity, and benefit—is the dominant terrain of modern influence. Military or economic strength is undermined without it.

Integrated Principle: Legitimacy as contested space. PRC and Russian narratives deliberately target the credibility and intent of U.S. efforts, exploiting mismatches between narrative and action.

Wargame Insight: Legitimacy was the gravitational force in every round of the wargame. Players who gained the support of local actors—through transparency, alignment with domestic values, and benefit sharing—were able to operate with sustained influence, even against materially superior adversaries. Conversely, teams that bypassed local legitimacy mechanisms—choosing speed or unilateralism—quickly saw access restricted, credibility eroded, and partner trust redirected toward competitors. The Confucius GPT was highly effective at weaponizing legitimacy gaps, offering culturally tailored narratives and rapid infrastructure deals that made Western offers seem conditional or insincere. In this contested arena, legitimacy is not a normative ideal—it is the terrain of maneuver.

DoD Alignment: U.S. military and interagency doctrine increasingly recognizes that we must win not just battles, but narratives. Doctrines like FM 3-24 on counterinsurgency and information operations manuals emphasize the importance of being seen as a legitimate actor—by local populations, allies, and even adversaries (U.S. Army, 2014; USSOCOM, 2018). Legitimacy affects access, trust, and the ability to sustain operations. Adaptive Power reinforces that legitimacy isn’t a side effect—it’s the battlespace itself. If an operation appears self-serving or opaque, competitors like the PRC will exploit that perception to delegitimize U.S. actions. True influence today requires visible fairness, transparency, and benefit-sharing.

Case Study 3: Competing Port Infrastructure in Fiji (FMFA 2024)

Context: The PRC funded and delivered rapid infrastructure upgrades in Fijian ports with visible, measurable effects—jobs, roads, and public announcements. PRC gained traction by appearing faster, simpler, and more visible to locals. U.S. efforts, though better engineered, were often perceived as elite-facing or transactional

Challenge: U.S. and allied infrastructure programs lagged, were bureaucratically complex, and often negotiated with elite intermediaries.

Action: Despite superior technical design, U.S. efforts were perceived as elitist and slow-moving. PRC efforts were seen as more legitimate in the public eye.

Doctrinal Insight: Legitimacy isn’t just ethical—it is operational terrain. Visibility, equity, and narrative coherence must accompany action. Influence that feels extractive will always be vulnerable to narrative attack.

- Modularity: Influence as a Flexible Architecture

Definition: Strategic tools must be agile, scalable, and combinable across diplomatic, military, economic, legal, and informational domains. Power must shift with changing terrain.

Integrated Principle: Resilience. Modularity creates redundancy, reduces brittleness, and ensures flexibility in complex environments.

Wargame Insight: Teams that adopted rigid influence strategies—locked into single domains or force-centric responses—were consistently outpaced by those who employed cross-domain modularity. The winning actors shifted seamlessly between legal signaling, economic inducements, technical enablement, and informational engagement based on the evolving board. In the real world, this mirrors how effective Indo-Pacific strategy requires agile integration of ISR support, humanitarian response, security cooperation, and digital connectivity. The GPT model excelled at identifying when its adversaries were stuck in doctrinal loops, often using lateral moves (like legal gray zones or economic pledges) to flip advantage without escalation. Influence is no longer about dominance in one domain—it’s about the fluid assembly of the right tools in the right combination at the right moment.

DoD Alignment: Modularity reflects the military’s increasing need to operate across domains and agencies—what’s called multi-domain operations (MDO) and whole-of-government coordination (Morris & Mazarr, 2019). Adaptive Power shows how influence must be composed of many small, flexible tools—legal advice, economic support, military presence, information campaigns—that can be used separately or together depending on the situation. This is similar to how the military builds interoperable task forces or deploys modular logistics that scale up or down. Modularity also enables partners to plug into the U.S. strategy without becoming dependent, strengthening resilience and alliance capacity.

Case Study 4: Quad-Supported Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness (Helmus et al., 2024)

Context: Pacific Island nations struggle with illegal, unregulated fishing—particularly by Chinese fleets—but lack ISR tools or enforcement capabilities. Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) programs leverage modular tools—tech sharing, training, legal cooperation, and ISR partnerships—to build layered deterrence across archipelagic states (Khayat, 2023).

Challenge: No single actor (U.S., Australia, Japan, India) could deliver a full solution. The threat was non-military but strategically corrosive.

Action: The Quad leveraged satellites (U.S.), training (Australia), legal frameworks (Japan), and coordination (Fiji/PNG) to build a layered MDA network.

Further, Case Study 2 PNG DCA integrated military access, legal reforms, infrastructure investment, and public diplomacy in a modular format. Its strength was not just access but the ability to scale elements based on PNG’s domestic tempo and legal frameworks (DOS 2023).

Doctrinal Insight: Modularity enables agility (USSOCOM 2020). Rather than a monolithic solution, each partner in an Indo-Pacific partnership for maritime domain awareness delivered domain-specific tools that formed a durable influence web-adaptive, scalable, and tailored to regional needs.

- Learning: Continuous Strategic Adjustment

Definition: In competitive environments, influence depends on iteration. Actors must observe, adapt, and evolve faster than adversaries.

Integrated Principle: Enabling influence. True strategic learning requires feedback from partners and the ability to empower local actors to innovate and respond.

Wargame Insight: Across years of Indo-Pacific wargame series, outcomes pivoted not on raw capabilities but on learning in-stride—teams that shed fixed assumptions, tested new ideas mid-game, and reoriented narratives consistently outmaneuvered status-quo thinking.

No strategy survived the midpoint of the wargame unless it evolved. The most successful teams were those that embedded internal red teaming, changed course when feedback indicated failure, and actively co-learned with partners. Static campaign plans led to rapid irrelevance, particularly when adversaries like the GPT model adapted narratives or asymmetric tools in real-time. In some games, teams that lost early rounds recalibrated through consultation and narrative reframing, ultimately securing regional legitimacy by the endgame. These cycles mirrored the real-world necessity for operational humility and doctrinal agility. Learning isn’t an after-action phase in Adaptive Power. It is a live operational function that determines whether influence persists or fractures under pressure.

DoD Alignment: The DoD now recognizes that learning during operations is essential—not just learning after they’re over. This is reflected in the push for adaptive planning, campaign assessments, and red-teaming. Special Operations Forces (SOF) doctrine, in particular, emphasizes “learning organizations” that can adjust in real-time, not just at the end of a deployment (USSOCOM 2020). Adaptive Power integrates this idea by requiring influence campaigns to include feedback loops with partners, civilian populations, and adversary reactions. This isn’t academic. It means actually changing approaches when conditions shift rather than staying locked into a failing strategy.

Case Study 5: U.S. and Philippine Partnership During the Battle of Marawi (USIG 2019)

Context: In 2017, ISIS-affiliated Maute militants seized the city of Marawi in the southern Philippines. The Philippine Armed Forces (AFP) faced a fierce urban fight with complex terrain, unfamiliar insurgent tactics, and high civilian risk.

Challenge: Initial AFP responses struggled with intelligence gaps, ISR limitations, and the difficulty of conducting precision operations in dense urban environments. There was also domestic political sensitivity around U.S. involvement, limiting overt presence.

Action: Rather than pushing a predetermined playbook, the U.S. provided modular, responsive support: real-time ISR via drones, technical assistance, and behind-the-scenes coordination through the Joint U.S. Military Assistance Group. Crucially, this support evolved over the course of the campaign based on AFP feedback. The U.S. shifted assets, adjusted targeting processes, and adapted advisory mechanisms in response to on-the-ground learning. Civilian evacuation, humanitarian support, and post-conflict stabilization were also co-developed in real-time.

Doctrinal Insight: The Marawi operation highlighted that influence and partnership are not static but must respond to evolving realities. U.S. support maintained political legitimacy while improving operational performance through adaptive consultation and in-stride learning. This became a model for future U.S.–Philippine collaboration, increasing trust and interoperability. Learning wasn’t confined to post-conflict lessons. It was a live function, enabling U.S. influence to scale with partner needs and battlefield conditions.

Comparing Adaptive and Smart Power

The following table presents a comparative analysis of Smart Power, Sharp Power, and Adaptive Power. It emphasizes doctrinal evolution, operational mechanics, and strategic relevance, ensuring direct ties to modern challenges in the Indo-Pacific and gray zone competition.

Table 1: A comparative analysis of Smart Power, Sharp Power, and Adaptive Power.

| Dimension | Smart Power | Sharp Power | Adaptive Power |

| Definition | Strategic use of both hard (coercive) and soft (attractive) power to influence and persuade | The manipulative use of information, legal structures, and covert influence to coerce or distort | Systems-based approach that synchronizes influence tools with timing, legitimacy, and learning |

| Strategic Objective | Build credibility and alignment without overreliance on force | Undermine, divide, or co-opt without overt conflict | Shape operational environments in real-time to maintain advantage and reinforce resilience |

| Core Instrument | Military presence, development aid, diplomacy, public messaging | State-controlled media, legal coercion, economic dependency, elite capture | Modulated legal tools, precision ISR, narrative shaping, civil-military partnerships, agile posture |

| Engagement Logic | Balance and attraction | Penetration and subversion | Agility, context alignment, and recalibration based on systemic cues |

| Influence Pathway | Institutional engagement, global norms, alliance-building | Targeted disruption of transparency, civil society, and sovereignty | Strategic timing, partner legitimacy, adaptive campaign design |

| Assumptions | Tools can be harmonized for broad legitimacy and trust | Fragile systems are exploitable through asymmetry and narrative distortion | Systems are interdependent and fragile, and can be shaped through credible and responsive influence |

| Strength | Integrates broad tools and promotes responsible leadership | Operates below conflict thresholds; exploits gray zones | Enables tempo control, coalition adaptation, and early influence ahead of escalation |

| Vulnerability | May lack agility in rapidly changing environments | Can provoke backlash or overreach; lacks sustainability | Requires deep situational awareness, trust-based access, and cross-domain fluency |

| Indo-Pacific | U.S. Millennium Challenge Compacts; Public diplomacy in ASEAN Islands security pact | PRC-Solomon Belt and Road port entanglements; legal warfare in South China Sea | U.S. support in Marawi; PNG Defense Cooperation Agreement; modular campaigning and wargaming lessons |

| DoD Implications | Supports strategic messaging, public affairs, and soft-hard balance | Highlights the threat landscape for IW, cognitive domain, and resilience planning | Reinforces Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2), IW annex, campaigning in competition, and deterrence-by-resilience |

Where Smart Power was an integrative blend and Sharp Power a disruptive breach, Adaptive Power is a choreography of coordinated influence.

Smart Power assumes that the right balance between hard and soft tools will achieve influence; Adaptive Power assumes that influence depends on timing, legitimacy, and contextual fit. Smart Power is strategic in orientation; Adaptive Power is operational and systemic, attuned to the current world of fractured alliances, polycrises, and perceptual warfare.

Operational Implications for the DoD in the Indo-Pacific

- Shift from Episodic Engagement to Persistent Presence

Adaptive Power Principle(s): Timing, Legitimacy

DoD Priority: Integrated Deterrence, Campaigning in Competition

Operational Implication: U.S. forces and interagency actors must maintain a forward presence that is locally resonant and continuously consultative. This means investing in sustained, low-friction activities, such as port visits, legal capacity building, data sharing, and border-security interfaces, that create influence ecosystems before crises happen. Commanders should prioritize engagements that map to local rhythms (e.g., disaster anniversaries or election cycles) rather than fixed U.S. calendar rotations.

- Build Influence Networks That Are Sovereignty-Respecting, Not Access-Extractive

Adaptive Power Principle(s): Context, Legitimacy

DoD Priority: Ally/Partner Empowerment, Networked Security Architecture

Operational Implication: Agreements and basing strategies (e.g., EDCA in the Philippines, DCA in PNG) must reflect deep legal, political, and cultural consultation, not just strategic utility. Military planners should involve local constitutional experts early and visibly, ensuring new facilities or access arrangements enhance host legitimacy and are seen as mutually beneficial. The key question is: Would the host government defend this partnership in a domestic political crisis?

- Treat Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) as an Influence Platform, Not a Sensor System

Adaptive Power Principle(s): Modularity, Legitimacy

DoD Priority: Resilience in the Contact Layer, Domain Awareness

Operational Implication: Quad- and partner-driven MDA platforms must evolve into sovereignty-enabling systems, not just ISR feeds. Offer partners real-time control, legal harmonization toolkits, and economic leverage tied to detected incursions. Use MDA as a doorway to legal empowerment, fisheries justice, and narrative control—not just maritime mapping.

- Weaponize Learning and Campaign Assessment

Adaptive Power Principle(s): Learning, Timing

DoD Priority: Adaptive Campaigning, Strategic Learning

Operational Implication: USINDOPACOM and component commands should integrate real-time campaign adjustment teams—specialists who monitor narrative feedback, partner reactions, and adversary counter-moves. Adaptive Power requires that planners and operators have the authority and tooling to course-correct mid-deployment, not wait for end-of-tour AARs. Learning must be fused with operational tempo.

- Build Modularity into Every Line of Effort

Adaptive Power Principle(s): Modularity, Learning

DoD Priority: Cross-Domain Synergy, Crisis Flexibility

Operational Implication: Every engagement—whether a humanitarian assistance mission, ship visit, or legal workshop—should have modular attach points across domains: can this activity enable information ops? Legal capacity? Infrastructure leverage? This requires interagency co-design and the ability to rapidly recombine tools. Influence should be scalable and reconfigurable—like a task-organized maneuver unit, but diplomatic and legal in form.

- Displace PRC Influence Indirectly Through Narrative and Network Seeding

Adaptive Power Principle(s): Legitimacy, Context

DoD Priority: Strategic Competition, Counter-Coercion

Operational Implication: Direct military competition with China in many Indo-Pacific locales creates escalation risks or legitimacy costs. Instead, PRC influence can be displaced indirectly by building micro-networks of legitimacy: cooperative media training in the Pacific, anti-corruption alliances, blue economy financing, and legal aid to fisheries ministries. These are small moves with outsized influence in fragile legitimacy environments.

Conclusion

Adaptive Power reframes influence not as a static toolset but as an evolving, learning-centric engagement model. Grounded in five interdependent pillars—Timing, Context, Legitimacy, Modularity, and Learning—it addresses the operational demands of the Indo-Pacific and broader strategic competition.

Wargames have validated the core of this doctrine: success is not found in dominance but in the right move at the right time, done with the right voice, the right partners, and the willingness to evolve. Adaptive Power is not a rejection of Smart Power but its maturation into an understanding of power that is better suited to a world in flux, not one in balance.

References

- Adams M. Five reasons American decline appears irreversible. The Hill 2024; 19 Jan. https://thehill.com/opinion/campaign/4414582-five-reasons-american-decline-appears-irreversible/.

- Canyon D. Competitive security gaming: rethinking wargaming to provide competitive intelligence that informs strategic competition and national security. Security Nexus 2020;21: http://dkiapcss.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/N2542-Canyon-Rethinking-wargames-new-2.pdf.

- Canyon D. Goldilocks Power and the Reform of Irregular Warfare in a Changing World. Security Nexus 2021; 22. https://dkiapcss.edu/nexus_articles/goldilocks-power-and-the-reform-of-irregular-warfare-in-a-changing-world/.

- Canyon D, Cham J, Potenza J. Complex security environments, strategic foresight and transnational security cooperation games. Daniel K. Inouye Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies, Occasional Paper, 2018;Sep:1-12. https://dkiapcss.edu/complex-security-environments-strategic-foresight-and-transnational-security-cooperation-games/.

- Department of Defense (DoD). National Defense Strategy of the United States of America, 2022. https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.pdf.

- Ducharme DR. Measuring strategic deterrence: a wargaming approach. JFQ 2016; 82: 3rd Qtr: 40-46. https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-82/jfq-82_40-46_Ducharme.pdf.

- Fiji Ministry of Foreign Affairs (FMFA). Fiji aims to further enhance its port capabilities, FMFA Blog, 2024. https://www.foreignaffairs.gov.fj/fiji-aims-to-further-enhance-its-port-capabilities/.

- Helmus TC, Grocholski KR, Liggett T, et al. Understanding and countering China’s maritime gray zone operations. Rand Corporation, 2024. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA2900/RRA2954-1/RAND_RRA2954-1.pdf.

- Herr R. In signing deal with China, Solomon Islands has broken the trust of its Pacific neighbours. The Strategist, 2022; Apr 6. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/in-signing-deal-with-china-solomon-islands-has-broken-the-trust-of-its-pacific-neighbours/

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. Joint Concept for Competing. 2023a. https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23698400/20230213-joint-concept-for-competing-signed.pdf.

- Joint Chiefs of Staff. JP 5-0: Joint Planning, 2023b.

- Khayat S. The Indo-Pacific partnership for maritime domain awareness. Pacific Forum, 2023. https://pacforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/PacNet48.2023.06.23.pdf

- Medcalf, R. Indo-Pacific Empire: China, America and the Contest for the World’s Pivotal Region. Manchester University Press, 2020.

- Morris LJ, Mazarr MJ, Hornung JW, et al. Gaining competitive advantage in the Gray Zone. RAND Corporation, 2019. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2900/RR2942/RAND_RR2942.pdf.

- Nye JS. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. PublicAffairs, 2004.

- Nye JS. The Powers to Lead. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2010.

- Olay M. Defense Secretary underscores DoD priorities during Pentagon Town Hall. U.S. Department of Defense, 2025; 7 Feb. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/4060150/defense-secretary-underscores-dod-priorities-during-pentagon-town-hall/.

- S. Army. FM 3-24: Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies, Marine Corps, 2014. http://www.fas.org/irp/doddir/army/fm3-24.pdf.

- S. Department of State (DOS). Papua New Guinea (23-816) – Defense Cooperation Agreement, 2023. https://www.state.gov/papua_new_guinea-23-816.

- S. Inspector General (USIG). Operation Pacific Eagle – Philippines. U.S. Department of Defense, 2019. https://oig.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2019-08/lig-oco-opep-June2019.pdf.

- summary of the Irregular Warfare Annex to the 2018 National Defense Strategy, 2020. https://media.defense.gov/2020/Oct/02/2002510472/-1/-1/0/Irregular-Warfare-Annex-to-the-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.PDF.

- Walker C, Ludwig J. The meaning of Sharp Power. Foreign Affairs, 2017; 16 Nov. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2017-11-16/meaning-sharp-power.

Published: June 25, 2025

Category: Perspectives

Volume: 26 - 2025

Author: Deon Canyon

Thank you, Dr. Canyon. The concept of Adaptive Power feels realistic and practical. It truly fits the unpredictable nature of today’s world.

excellent