By Canyon D, Allen E, Long M, Brown C [*]

Introduction

Like all natural resources on Earth, fish are finite. While aquaculture now supplies about half of the fish caught annually, and while estimates of amounts being fished vary widely, data suggest that, globally, over one-third of fish stocks are harvested beyond biologically sustainable limits. The problem of overfishing is rapidly getting worse as the mass of captured fish increased four-fold over the past six decades, particularly in tropical oceans. Trends indicate a non-sustainable trajectory for fish populations, worldwide, with increases in per capita fish consumption outstripping human population growth. In 2018 (the most recent year for which data are available), about 156 million tons of fish, 20.5 kg per person, were consumed by people, with another 22 million tons used for products such as fishmeal and fish oil. About 70% of the fish taken were from the Indo-Pacific.

Nearly half of the world’s population consumes 20% of their animal protein from fish. Thus overfishing, with the attendant risk of sudden fish population collapse, as happened on the Grand Banks in the North Atlantic with cod, has critical food security implications. Beyond the impact on fish populations and possibly on human nutrition, some types of fishing, such as deep-sea bottom trawling, are environmentally unsustainable as they damage fragile habitats containing unique biodiversity including millenary deep-sea corals.

This paper explores the perpetrators of overfishing, the role of fisheries crime in overfishing, efforts to combat overfishing including legal frameworks, approaches of the US and its partners, and international security cooperation on fishing subsidies, and provides seventeen policy recommendations.

Who is overfishing?

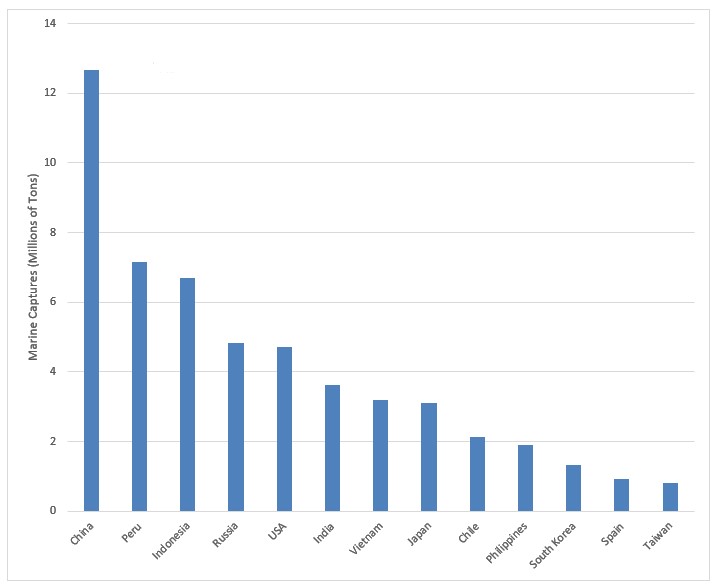

Figure 1: National shares of marine captures

A relatively small number of countries are responsible for much of the global fishing (Figure 1). Recent technological developments in machine learning and satellite data now provide a novel method to examine fish populations and fisheries that allows a far more accurate determination of fishing effort across the globe at the level of individual vessels than was possible a few years ago. Until very recently, the global make-up of fishing fleets was largely unknown, but new technologies, using the Global Fishing Watch (GFW) database, which uses automatic identification systems (AIS) and vessel monitoring systems (VMS) can track individual vessel behavior, fishing activity, and other characteristics in near real-time. These tools now enable detailed analyses of issues such as the economic rationality of fishing over vast swathes of Earth’s surface, and can allow addressing of the key question of whether government subsidies enable current levels of fishing.

AIS databanks show that in both national waters and on the high seas, most fishing effort is conducted by vessels flagged to higher-income nations with 86% attributed to China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and Spain, in rank order, and only 3% attributed to lower-income nations. Most fishing activity takes place in the Pacific (61%), the Atlantic (24%), and the Indian Oceans (14%). The mismatch evident between reported marine captures shown in Figure 1 and the ranked order of fishing effort, for all nations but China, are testimony to the extent that accurate fishing data are not yet available and there are many non-transparent, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities.

As evidence of the incredible inequities in the fishing business, vessels flagged by high-income foreign countries were not only dominant in their own exclusive economic zones (EEZs), but also in the EEZs of lower-income nations where they captured the majority of fish to the detriment of local fishing industries. As local fish catches fall below economic viability due to these foreign fishing vessels, maritime crime can increase as fishers turn to piracy and smuggling to survive.

Fishing Crime

The AIS and VMS technologies have only been able to identify corporations responsible for 61.5% of fishing effort due to 20% of ships on the high seas being unequipped with AIS and the rest turning off their AIS. It is believed that some monitored vessels, but particularly these unmonitored vessels engage in IUU fishing methods, which represent a threat to national and global security as they account for significant economic loss, weaken national sovereignty, and destroy a precious limited global resource. One in five fish caught may originate from IUU fishing. US Coast Guard Commandant ADM Karl Schultz said, “IUU fishing has replaced piracy as the leading global maritime security threat. If IUU fishing continues unchecked, we can expect deterioration of fragile coastal states and increased tension among foreign-fishing nations, threatening geopolitical stability around the world.”

Overfishing does not always equate to IUU fishing; however, IUU fishing is a significant contributing factor to overfishing and the depletion of global fish stocks. Illegal fishing using prohibited methods or equipment typically results in excessive bycatch through non-selective means, upsetting the fragile ecological balance. Fish illegally caught in protected areas or in another nation’s EEZ undermine regional and national management efforts in sustainability. Unreported fishing can include failing to report, misreporting, or under-reporting practices; all of these result in flawed data that prevent informed decision-making by management authorities when determining catch/size limits and the amount of fishing licenses issued. Unregulated fishing refers to vessels without nationality, areas not covered under existing national or Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) management measures, and species with insufficient regulatory oversight that may be subject to exploitation.

The world’s dependence on fish as a vital protein source is an incentive for the global community to monitor and ensure robust fish stocks as a matter of food security. Unfortunately, from 1974 to 2017, the percentage of fish stocks within biologically sustainable limits dropped from 90% to 65.8%. Conversely, the world’s human population continued to increase, placing additional pressure on stressed fish stocks. While aquaculture is alleviating some of the demand on wild-caught fish, proper national and regional fisheries management is vital to ensure that sustainable policies are implemented and enforced appropriately to prevent overfishing.

Combatting Overfishing with Legal Frameworks

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) presents a structure for fisheries governance by distinguishing between state-managed fisheries within the 200 nautical mile EEZ and fisheries outside the EEZ on the high seas. It provides for migratory fish, such as tuna, that travel between different EEZs and high seas, fish that straddle the EEZs and the high seas, and fish, such as eels and salmon, that migrate between the sea and freshwater. Lastly, it requires countries to cooperate with one another to conserve and manage fish in the high seas.

Modern fishery governance is characterized by guiding principles, and policy and regulatory frameworks that connect government with corporate actors. Fishery governance includes national policies and legislation or international treaties as well as customary social arrangements. At the international level, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is the “only source of global fisheries and aquaculture statistics.” This repository is informed by the collection and analysis of how nations engage in responsible and sustainable fisheries management around the world.

The UN Fish Stocks Agreement goes further than UNCLOS by increasing cooperative action in the management of fisheries resources. It advises nations on how they should manage highly migratory fish stocks in cooperation with each other, and highlights the importance of RFMOs.

RFMOs are international organizations that typically focus on the sustainable management of all fishery resources or a particular species within a specific area. RFMOs provide information on corporate actors; however, their data are often incomplete or inaccessible in that they register shell companies that obscure corporate actors, they do not all make vessel ownership available, and/or they do not publish public vessel registries.

Within the Indo-Pacific, there are nine RFMOs.

- Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC)

- Indian Ocean South East Asian Marine Turtle Memorandum of Understanding (IOSEA)

- Agreement on the International Dolphin Conservation Program (AIDCP)

- Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC)

- North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC)

- Convention on the Conservation and Management of Pollock Resources in the Central Bering Sea

- Pacific Salmon Commission (PSC)

- Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC)

- International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC)

Given that global fish stocks are in a rapidly deteriorating condition, these fisheries governance structures are clearly failing in their objectives and require attention. For instance, only ten of the 17 RFMOs that cover high seas globally have carriage requirements for an onboard observer, and only one has a ban on transshipment; a practice that obscures the source of a significant portion of illegal and unreported fishing activity and provides a pathway for illegally caught fish to enter the global seafood market. It may be that onboard observer requirements are not being pursued since they are a widely corrupted monitoring mechanism.

Combatting Overfishing – Approaches of the US and Partners

In the United States, the US Coast Guard and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are two federal agencies at the forefront of combatting IUU fishing, with the US Coast Guard having the lead for at-sea enforcement of living marine resource laws.

In addition to protecting US sovereign waters from overfishing, the US recognizes that a global approach is needed to effectively combat the transnational nature of IUU fishing. As such, the US Coast Guard and NOAA are both involved in a constellation of international counter-IUU fishing operations and partnerships. These include:

- Pacific Quadrilateral Defense Coordinating Group (Pacific QUAD). The US Coast Guard serves as the US Indo-Pacific Command representative to the Pacific QUAD, a collaborative effort with Australia, France, and New Zealand aimed at coordinating and strengthening maritime security in the South Pacific. Pacific QUAD efforts to combat overfishing include joint patrols to ensure compliance with international fisheries agreements.

- Operation North Pacific Guard. This is a multilateral enforcement operation in partnership with Canada, China, Japan, South Korea, and Russia to tackle all IUU fishing threats in the North Pacific Ocean.

- Shiprider Agreements. The US Coast Guard partners with Pacific Island Nations through bilateral agreements known as Shiprider Agreements. These allow partners nations to enforce their own domestic laws by having their law enforcement officials onboard a US Coast Guard vessel or alongside their boarding team.

- Port State Measurements Agreement (PSMA). The United Nations enacted the PSMA to prevent IUU fishing through the adoption and implementation of effective port state measures to help ensure the long-term conservation and sustainable use of living marine resources.

- NOAA serves as the lead agency for enforcing PSMA in the United States and its Territories, which includes setting standards for exercising port state controls over foreign-flagged vessels seeking entry into US ports and over those vessels’ activities while in port. Through information sharing, vessels on IUU lists are identified and prevented from offloading illegally caught catch in ports, thereby increasing the costs of IUU fishing through diminished demand.

- Counter IUU-Fishing Capacity Building. Through various technical assistance and training workshops, NOAA provides foreign organizations governments, organizations, and communities with the tools, resources, and information sharing avenues to allow them to address complex IUU fishing issues.

Foreign partners and organizations recognize that IUU fishing poses pervasive security, economic, and environmental threats to national and regional interests and have taken a series of actions to counter this predatory and irresponsible behavior. For example, Australia enacted their Pacific Maritime Security Program to provide patrol vessels and aerial surveillance assets to a number of Pacific Island countries. These assets allow these Pacific Island countries to locate and stop illegal activity within their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and adjacent high seas through increased maritime domain awareness.

In addition, 18 member nations of the Pacific Islands Forum ratified the Boe Declaration, which affirms climate change as the single greatest threat to the livelihoods, security, and wellbeing of Pacific Islanders. Recognizing the deleterious effects of climate change on fish stocks and food security, the Boe Declaration’s Action Plan includes strengthening efforts to combat IUU fishing through enhanced monitoring and surveillance capabilities.

Finally, the United Nations, in addition to enacting the PSMA, formulated a series of international agreements to address the responsible management of fisheries to include the Fish Stocks Agreement, Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, and Voluntary Guidelines for Catch Documentation Schemes.

Combatting Overfishing with International Security Cooperation

The 1982 UNCLOS agreement did not include provisions to protect deep-sea fishing because it was expected to remain uneconomical. However, new harvesting technologies and national subsidies have combined to result in the unsustainable exploitation of this vulnerable environment. Technologies, such as machine learning and satellite data via GFW and AIS, also have a positive effect as they begin to shed light on the hitherto unknown details and economics of high-seas fishing activities.

In an analysis of the profitability of high-seas fishing from 2014 data, six countries (China, Taiwan, Japan, Indonesia, Spain, and South Korea) accounted for 77% of the global high-seas fishing effort. The study examined vessel-level data on ship length, tonnage, engine power, gear, flag state, trip-level fishing and transit tracks, speed, and other factors that affect the costs of fishing. This data was matched with the total fisheries catch from the high seas and its landed value in US$. Five of the above countries accounted for 64% of the global high-seas fishing revenue: China (21%), Taiwan (13%), Japan (11%), South Korea (11%), and Spain (8%).

Based on these numbers, researchers estimated that high-seas fishing profits (without accounting for subsidies) ranged between −$364 million and +$1.4 billion with most negative returns accruing from China, Taiwan, and Russia. Thus, fishing operations by those countries were not viable and were only in existence because government subsidies, estimated at $4.2 billion, far exceeded any net economic benefits of high-seas fishing. A more recent study in 2018 estimated that 54% of current high-seas fishing activities were not economically viable without government subsidies.

Subsidies are used by governments to reduce the cost of fishing and keep the industry viable; however, they are leading to overfishing caused by overcapacity. Eliminating fishing subsidies would almost eliminate high-seas overfishing and prompt multinational commitments (e.g. Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the Sustainable Development Goals) to address capacity-enhancing subsidies.

Fishing subsidies come in three categories: Ambiguous – assistance, community development, vessel buybacks; Beneficial – research, management, and protection; and Capacity-Enhancing – boat building, fisheries development, fishing access, fishing port development, fuel, marketing, storage, tax exemptions. Fuel subsidies, tax exemptions, and fisheries management are the largest type of fishing subsidies by far.

Asian governments pay the most subsidies to the private sector at 55% of the total ($35.4 billion in 2018) and of all nations, China pays the highest subsidies at 21% of the total followed by the US at 10% and South Korea at 9%. However, the US spends a majority of its subsidies on beneficial areas while China spends almost all of its subsidies on unsustainable and unprofitable capacity-enhancing areas.

The World Trade Organization has been thinking about, but taking no action on fishing subsidies since the Doha Development Agenda was launched in 2001. World leaders have turned in expectation to the WTO to set international rules that reduce unsustainable fishing subsidies as it is perhaps the only agency that can develop and enforce such global agreements. In 2015, trade ministers agreed to conclude a fisheries subsidies agreement by 2020 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals; however, the Covid pandemic delayed this action.

In the forthcoming 12th Ministerial Conference WTO meeting in late 2021, an agreement will be sought to govern fishing subsidies to make fishing more sustainable, eliminating IUU in the high-seas, and prohibiting subsidies that contribute to overcapacity and overfishing. One of the most difficult issues has been how to preserve the overall objective of ocean sustainability while not impacting the livelihoods and food security of poor and vulnerable artisanal fishers in developing and least developing country WTO members.

Policy Recommendations

Fisheries management

- Simplify fisheries management – contradictory directives from the various agencies involved in fisheries management, and the lack of communication among them, place a burden on monitoring and enforcement that impacts compliance. Fisheries approaches are best integrated into broader planning and governance frameworks to reduce the problems of acting in isolation.

- Reduce gaps in geospatial management – Marine Protected Areas, fishing closures, and RFMOs that manage bottom fisheries and species other than tuna provide incomplete spatial coverage, however, tuna coverage is fairly complete.

- Holistic assessment of sustainability – as fisheries are increasingly overfished, monitoring must be upgraded to include ecosystem indicators that assess diversity in species and habitats that are essential to maintain ecosystem services.

- Improved information – knowledge of the oceans and of fisheries activities are both fundamental to making critical decisions that aim to balance exploitation with sustainability. Transparency is required to increase accountability and ensure that fisheries industries uphold sustainable conservation objectives.

Fisheries Politics

- Identify and prioritize information that is useful for managers and policy-makers, for this underpins international collaboration and decisions on how funding is directed. Improving success in this endeavor requires fisheries policy and management decisions to be inclusive, evidence-based, and considerate of local and traditional knowledge.

- Improve maritime domain awareness in governments and general populations to increase public support and government ownership of the fisheries agenda, and political will to improve implementation of existing policy frameworks, and support policy innovation for emerging challenges.

- Non-traditional maritime security is a cooperative endeavor designed to reduce or eliminate maritime contingencies. Security cooperation through bilateral and multilateral agreements is the best way to combat non-traditional maritime threats, especially for smaller nations with limited resources.

Fisheries Protection

- Reduce gaps in protection – update international triggers for action to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems against harmful human activities such as pelagic fishing and seabed mining.

- Persist in efforts to control IUU fishing by working towards the ratification and implementation of the PSMA by all flag, port, coastal, and market States.

- Standup national Maritime Fusion Centers capable of making sense of MDA data on drug and human trafficking, fisheries crime, incidents at sea, and environmental hazards, and that is capable of fusing this information to create new intelligence for enforcement agencies and policymakers.

- Encourage other nations to consider pursuing collaborative Shiprider agreements with other like-minded partners and allies to protect fisheries and strengthen regional stability.

- Require the International Maritime Organization to evaluate changes to AIS carriage requirements to include vessels smaller than the 300 G.T. threshold on international voyages and 500 G.T. threshold on domestic voyages. Alternatively, standardize VMS carriage requirements at a higher level than the current national/regional requirements that vary on vessel size and equipment standards.

Fisheries Finances and Work Practices

- Move noble statements, such as the definition of Blue Economy by the World Bank from an unrealized and ignored ideal to reality through enforceable international agreements.

- Ensure livelihoods, wellbeing, and quality work are guaranteed in the fisheries sector through appropriate governance and management that involves stakeholders, secures human rights, promotes gender equity, and improves access.

- Implement the small-scale fisheries (SSF) guidelines to improve policies, information, communication, capacity, and support for SSF actors. This includes increasing financial support for this sector to improve fisheries management in the context of the blue economy.

- Increase international pressure on the WTO to eliminate capacity-enhancing subsidies and port-networks that support unsustainable fisheries practices to preserve a natural resource for people who depend on seafood for their nutrition and livelihoods.

- Redirect public funds that are spent on capacity-enhancement subsidies that compound resource-exploitation problems to beneficial subsidies that promote resource conservation and improved management, or to increase economic opportunities in other industries for residents of fishing communities.

[*] Dr. Canyon, Dr. Allen, Capt. Long, and Lt. Cmdr. Brown are professors at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies (DKI APCSS) in Honolulu, USA. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the DKI APCSS or the United States Government. October 2021

Published: October 22, 2021

Category: Perspectives

Volume: 22 - 2021