By James R. Sullivan

WSD-Handa Fellow

Abstract / Summary

Stories are at the core of our understanding of humanity, as well as central to many concepts at the heart of International Relations theory. The Chinese Communist Party has been adept at story telling for many years and for many purposes inclusive of intra-elite competition, maintenance of regime support, and tactical negotiations. These stories become especially critical during periods of regime transition, as we witnessed during the recently concluded Twentieth National Party Congress.

This paper leverages Natural Language Processing techniques applied to the GDELT database to quantify tones expressed on a variety of topics, targeting a range of both internal and external audiences. We show four facts: 1) China only began telling a more negative narrative regarding the United States post the beginning of the COVID pandemic in late 2019, but not prior; 2) China’s tone regarding the United States was consistent and relatively neutral across its civilian and military populations till late 2019, at which time the civilian tone became far more negative than the tone expressed to their military population; 3) XI Jinping’s tonal difference when discussing Taiwan across internal vs. external audiences is now at the highest divergence recorded; 4) Significant tonal differences are shown across various members of the previous Standing Committee. The tone for Xi Jinping has historically been the most positive but dipped into negative levels three times in 2022.

Keywords

National Security Strategy, Grand Strategy, Great Power Competition

Acknowledgements

Kumar Vemuri, Ian Johnston

Introduction

The power of the stories that sit at the center of human existence has been understood since the writing of Plato’s Republic in 380 B.C., extending on to the present day with psychologist Robyn Dawes suggesting that “humans are primates whose cognitive capability shuts down in the absence of a story”. (Dawes, 1999). This concept has also been widely applied in the realm of geopolitics, central to concepts such as soft power (Nye, 1997) as well as the distinction between structural security dilemmas (which exist in the “real” world, or Jervis’ operational milieu) vs. perceptual security dilemmas (occurring in Jervis’ psychological milieu). (Jervis et all, 1985) Analysis of the stories a country tells itself and others can even provide evidence of a country’s ambition to become a great power. (Miller, 2021)

But…what if you could control the shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave? (Plato, 1888)

The Chinese Communist Party has been actively creating, monitoring, and modifying the stories it tells the people of China for many years. This capability has allowed it to leverage public opinion in ways that both enable as well as constrain optionality. Stories can create action – “Where there is such coherence in narrative, the results can be highly compelling in terms of mobilization”. (Betz, 2008) This directed mobilization of public opinion can serve multiple strategic goals. First, it may shore up regime support, as shown in a clear historic pattern of blaming “hostile foreign forces” during periods of regime legitimacy challenge. (Johnston, 2017) Second, it may serve strategic purposes in negotiations, with leaders arguing that they cannot offer further flexibility on an issue without the risk of public backlash, in line with Fearon’s concept of “tying of hands”. (Fearon, 1997). Successful execution of such a strategy, however, requires the guiding hand to remain hidden. This is not always the case, as noted regarding Beijing’s narrative around the 2011 incidents in the Senkaku / Diaoyu Islands when it was suggested that “Beijing might have a point when saying it had to answer to public sentiment at home, but such a sentiment was at least in part its own creation to begin with”. (Sun, 2011)

Methodology

This paper applies Natural Language Processing techniques to the GDELT database (GDELT, 2022) in order to analyse the stories that China is telling, and to whom; across topics, publications, target audience, and language. We quantify Pure Tones, or the tone used in all articles about a particular topic, as well as Volume Weighted Intensity Tones, which weight Pure Tones by the quantity of their instance.

Publications can themselves be used as a proxy for the target audience. We analyze the People’s Liberation Army People’s Daily (here) to understand the stories told to China’s military, vs. the People’s Daily (here) to understand stories told to the general public. Measuring the differences between the two narratives may drive insight.

Lastly, analyzing tones present in different language publications from the same source (for example the People’s Daily in English (here) vs. Mandarin (here)) can be a proxy for a domestic vs. an international target audience.

The stories told now matter

This analysis is pursued at a critical juncture in time. Leadership transitions trigger a period of intra-elite competition that has historically been a primary source of regime risk in autocratic regimes. (Johnston, 2017) These regimes typically secure elite support through the transfer of “rents” which can be either economic (access to investments, liquidity, currency conversion etc.) or political (promotions, more senior posts within the Government & Party). (Dixit, 2009) The current transition period is the first where a change in leadership, and therefore changes in rent transfers, occur during a period of declining economic growth. Declining rent transfers may increase the risk of intra-elite challenges which, in turn, may create pressure to pursue diversionary tactics to drum up popular support to mitigate these elite challenges. This is not a new concept, sitting as it does at the core of teachings as far back as Machiavelli. (Machiavelli, 2005) Recent academic work suggests that up to 40% of the conflict that China has initiated vis-à-vis the United States has been coincident with periods of declining rent transfers. (Baggot, 2016)

Narrative analysis can help us understand who is telling what story to who, and where opinion is lagging or leading various narratives. This in turn can help us understand if there is a pivot to a new group of supporters during periods of regime transition, as well as the existence of the type of diversionary tactics that might be pursued to reduce intra-elite challenges.

This paper presents four facts that are quantified through NLP / narrative analysis and suggests questions which may be consistent with these facts.

Fact #1: China’s negative story regarding the United States is new

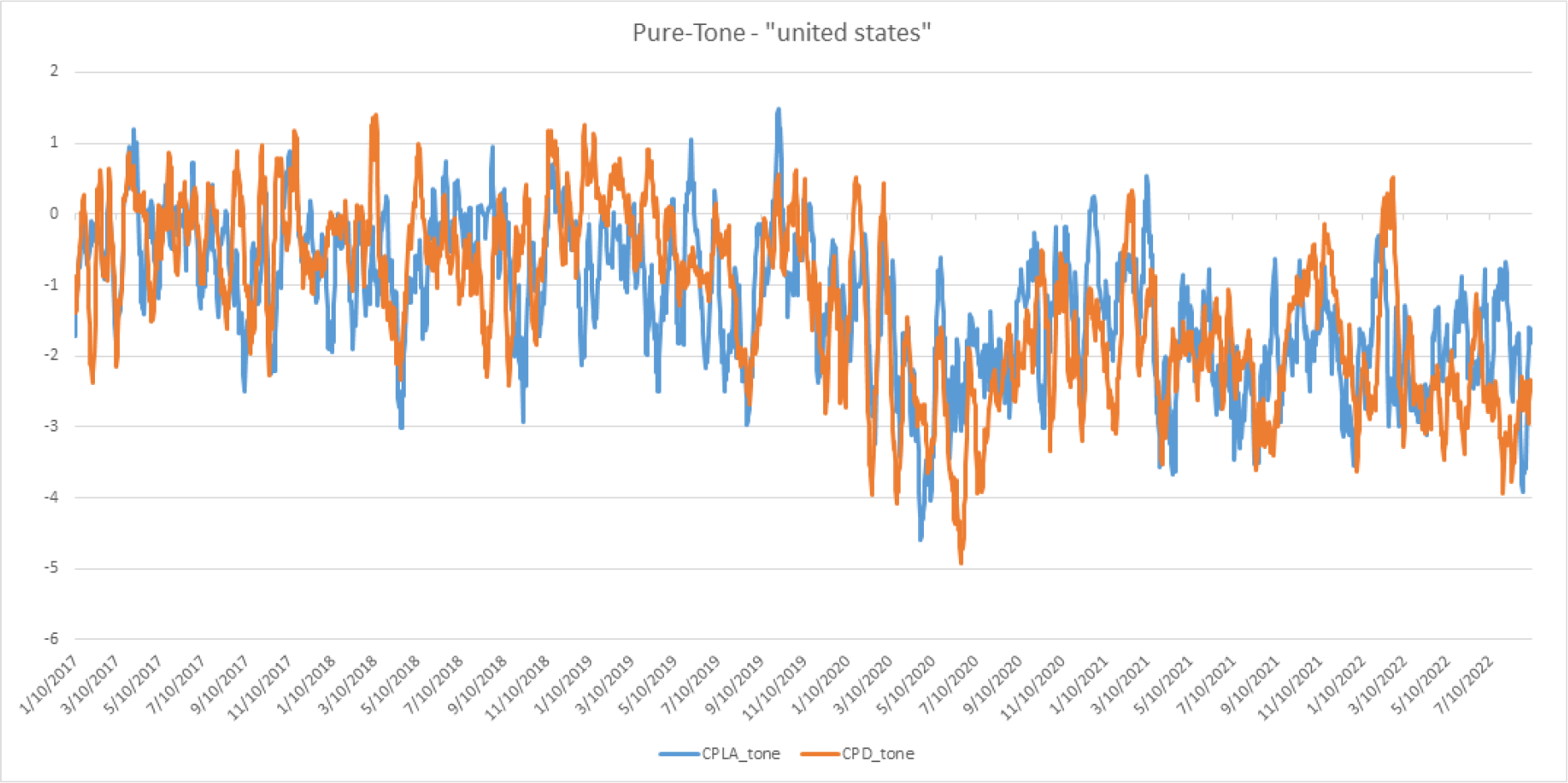

Escalating tensions between China and the US have been in place for some time. The tone measured in narratives regarding the US, however, remained only mildly negative from 2017-2019. The Pure Tone of stories about the United States in the People’s Daily (the orange line in the chart below) as well as the PLA Daily (blue line) ranged roughly from +1 to – 2 during this period of time (larger number tones are more positive, negative number tones are more negative). A change occurred coinciding with the beginning of the COVID pandemic in late 2019 / early 2020, when the range dropped to 0 to -4.

Source: Vemuri, Johnson, Sullivan, GDELT

The fact is that stories that China told its people about the United States inflected negatively only in late 2019, despite rising tensions in the preceding years.

The open question is whether this was scapegoating. Autocrats frequently attempt to increase popular support during periods of regime transition to stave off elite competition. (Geddes, 2009) Given the recently completed National Party Congress (Zhu, 2022) it is possible that the government would more aggressively highlight external enemies to shore up regime support, per Johnson has mentioned above. The fact that this negative tone began to occur coincident with the COVID pandemic outbreak is also consistent with the idea that China was attempting to shore up regime support during a period of domestic turmoil.

Fact #2: China tells a different story to its military and civilian populations

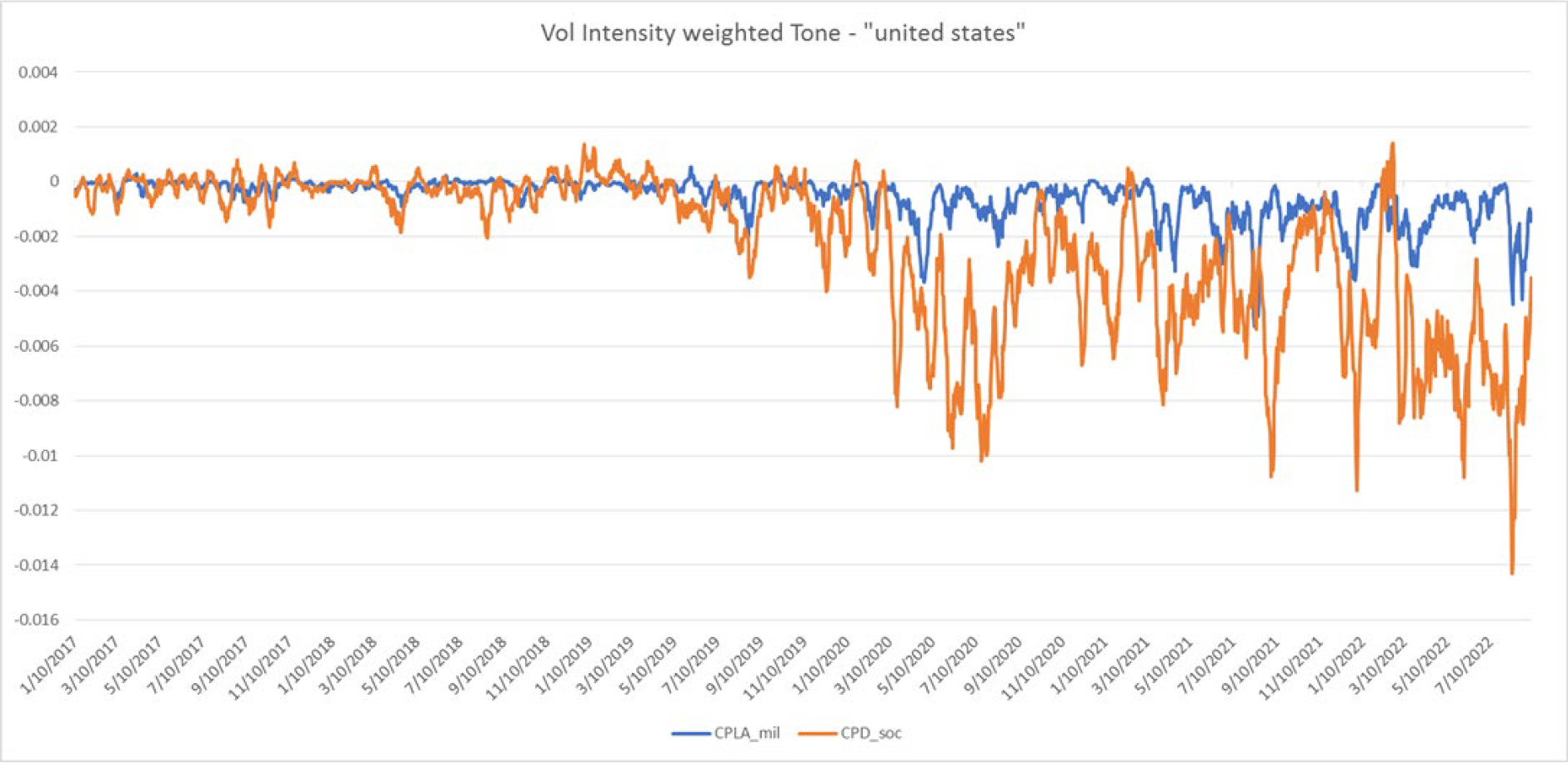

We next weight the Pure Tone expressed by the volume of stories. This gives us a Volume Intensity Weighted Tone statistic, which in this particular analysis changes the picture in a meaningful way. Per the chart below, the Volume Intensity Weighted tone of the stories told to the general public (orange line, representing the People’s Daily) have become much more negative relative to the stories told to a military audience (blue line, representing the People’s Liberation Army Daily).

Source: Vemuri, Johnson, Sullivan, GDET

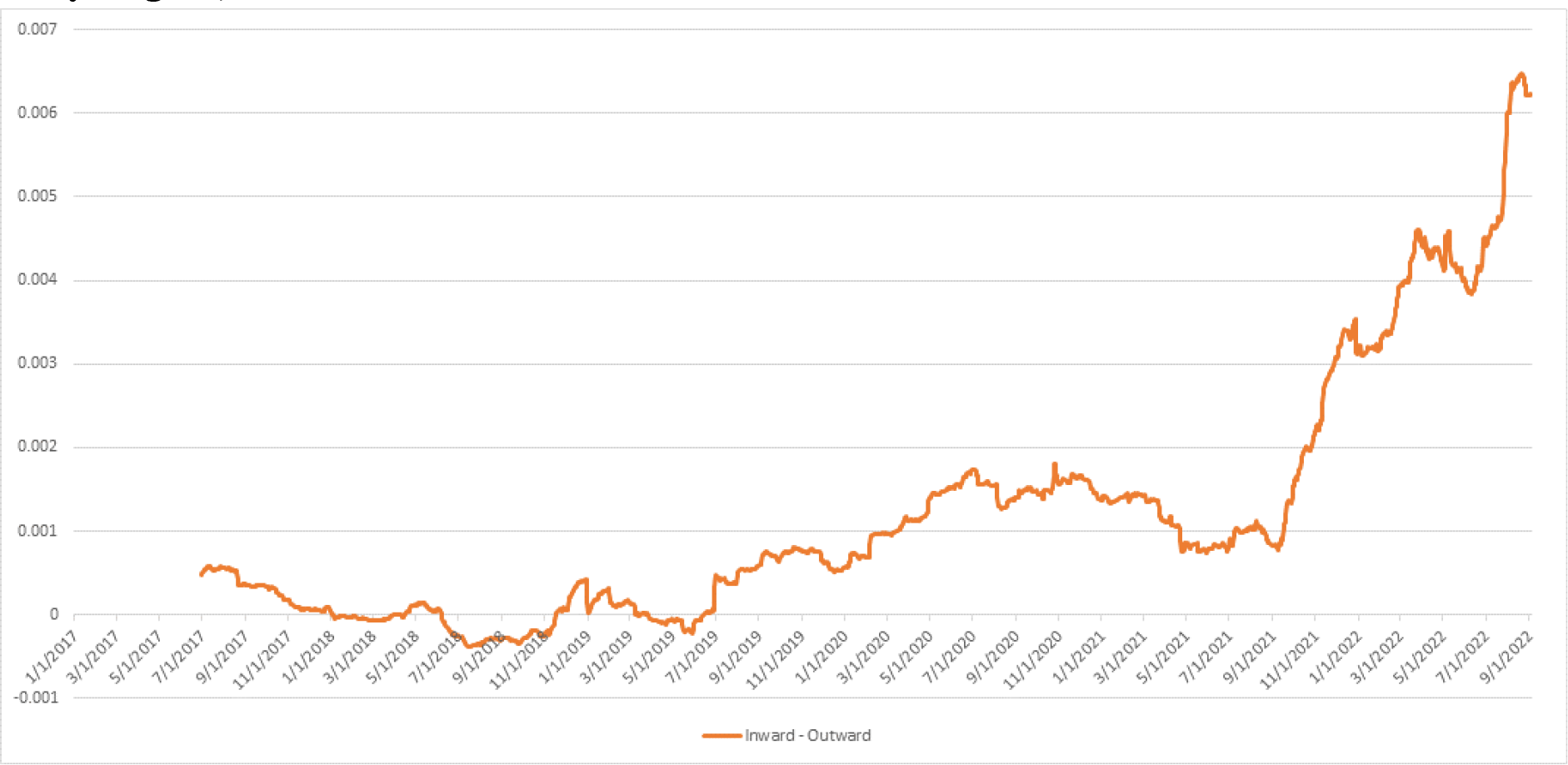

The chart below isolates this effect by calculating the difference between the Volume Intensity Weighted tone used with a civilian vs. military audience, and adds a rolling 12 month average. This highlights the increased negative civilian vs. military sentiment towards the US post January 2020, a slight rebound in July of 2021, and another downturn in the spring of 2022.

Volume Intensity Weighted Tone for term “United States” (PLA Daily – People’s Daily)

Source: Vemuri, Johnson, Sullivan, GDELT

The fact is that the People’s Daily began publishing a large volume of negative stories regarding the United States targeting the general population of China in early 2020, while this volume of negativity was avoided in articles targeting its military (as proxied through the PLA Daily).

The open question is whether this illustrates an attempt to shore up popular support while avoiding putting the military on a war footing. The suggested conclusion of this analysis is that the data above is consistent with, but not dispositive of, the idea that China is pursuing diversionary tactics rather than preparing for actual conflict in the short term. Diversionary tactics should generate maximum domestic impact at limited international costs, i.e. should be high profile domestically, without materially impacting facts on the ground offshore. The recent actions post Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan indeed exhibit many of these characteristics. PLA actions were broadly and aggressively covered across Chinese social media and print assets, without doing anything that might prove irreversible.

Fact #3: Countries often tell an onshore and offshore version of stories

We next examine the stories told about specific topics domestically vs. internationally. One clear example of this are stories about Xi Jinping and Taiwan. The chart below shows the Volume Intensity Weighted tone for stories told domestically (Inward audience, proxied by the Mandarin version of the People’s Daily) vs. Internationally (Outward audience, proxied by the English language version of the People’s Daily). The gap currently sits just off the highest level seen over the past 5 years, i.e. the story told onshore is the most different (in this case, more positive) to the one told offshore at present (in this case, more negative), vs. anytime over the past five years.

Volume Intensity Weighted Tone for “Xi Jinping + Taiwan” (People’s Daily Mandarin – People’s Daily English)

Source: Vemuri, Johnson, Sullivan, GDELT

This can perhaps be seen as an index of potential tension levels (with more back testing required). Narrative differentials may begin to peak during periods of rising tensions and fall during periods of calm (where there is little requirement to differentiate stories told to each audience). This remains a topic for future research.

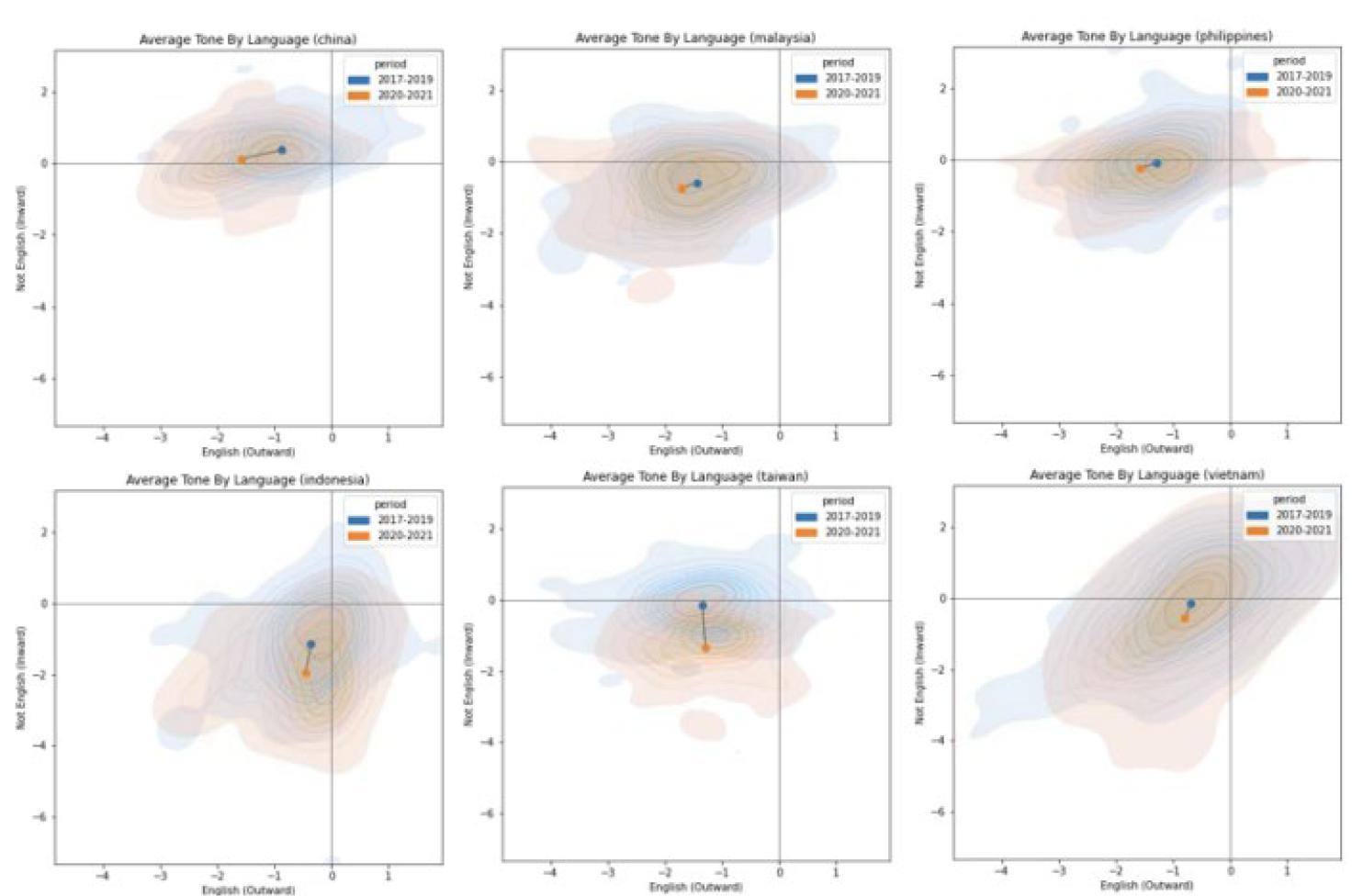

Similar time series analysis can be run for an issue across multiple countries. The charts below show Volume Weighted Intensity Tone regarding “South China Sea” in six countries, across local language press (y-axis) and local English language press (X-axis). China is the only country with a positive local language press tone; China, Malaysia and the Philippines shows significant negative movement in English language tones during the study period, while Indonesia, Taiwan and Vietnam all saw more local language tone degradation.

Source: Sullivan, 2022

The fact is that stories told by China regarding Taiwan have seen a significant difference in tone between those told to a domestic vs. an international audience. Similar shifts in relative tone can also be seen across a host of other countries on a range of issues.

The question is if these rising narrative gaps can be used as a more accurate predictor of conflict risk, vs. solely looking at tone changes aimed at one or the other audience. This will take more work to explore.

Fact #4: Significant tonal differences exist across senior Chinese leaders

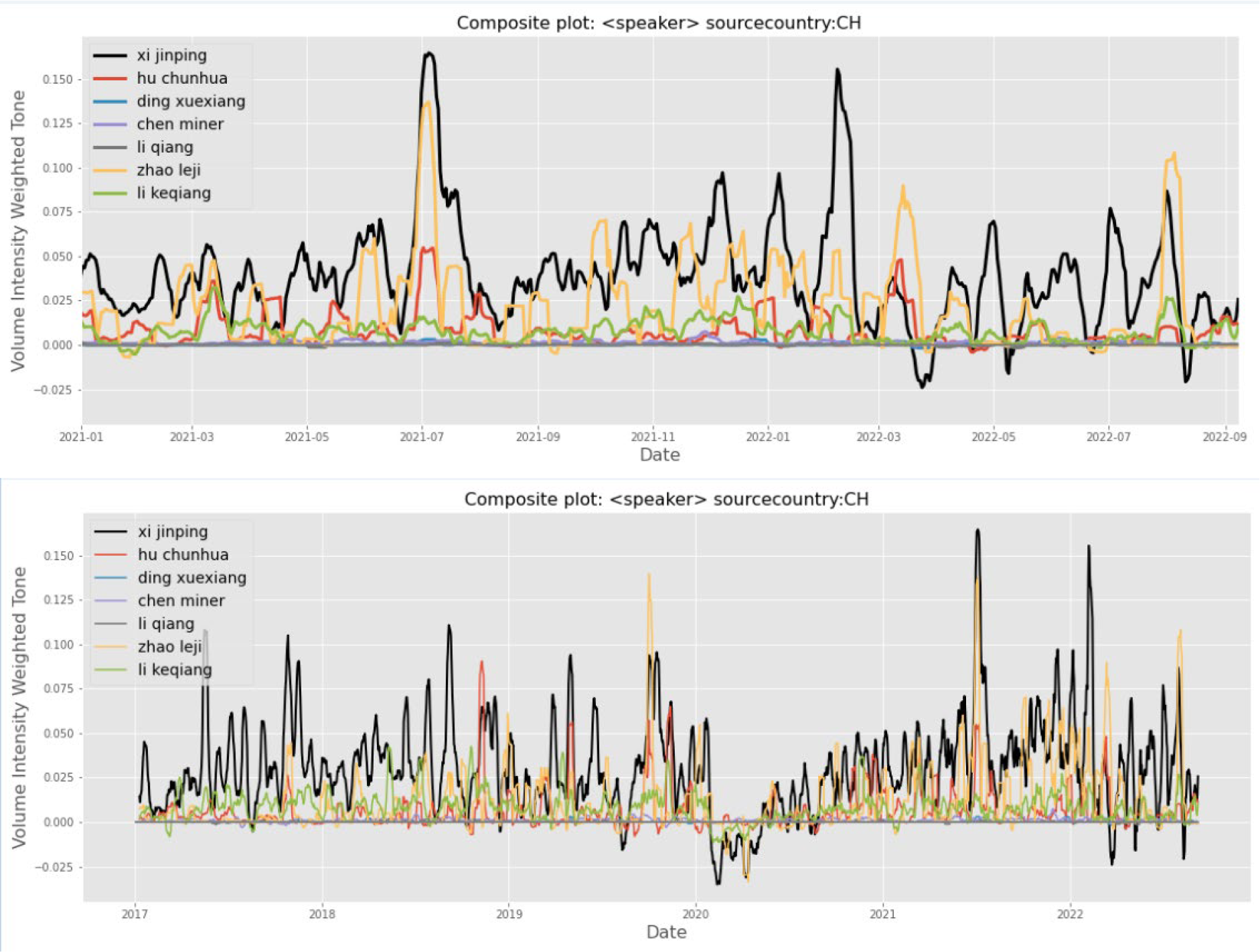

We can also leverage narrative analysis to try and better understand the relative momentum of senior leaders, an issue of particular importance during leadership transitions. The charts below (top chart zeroing in on 2021-present, the bottom chart showing 5 year trends) show Volume Intensity Weighted tone as expressed in the overall Chinese press. Not surprisingly, Xi Jinping generally shows the highest scores which are generally positive (although we note three negative tone periods for the first time within 2022). Zhao Leji interestingly has the second highest positive tones exhibited.

Source: Vemuri, Johnson, Sullivan, GDELT

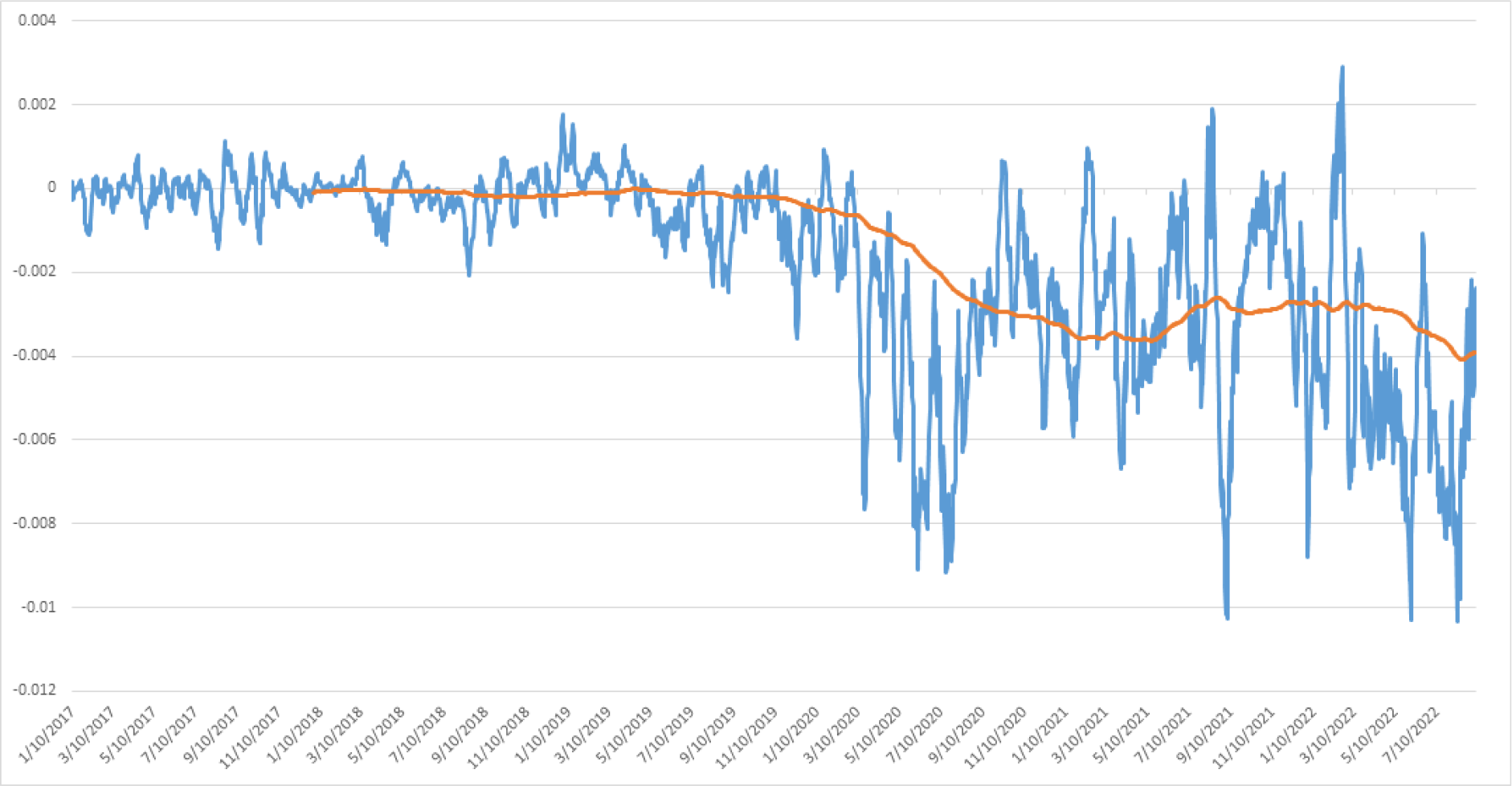

An additional approach to this data is to examine relative sentiment. The chart below shows the Volume Intensity Weighted tone for Xi minus that for Zhao. A rising line represents sentiment shifting more in relative favor of Xi, a falling line represents sentiment shifting in relative favor of Zhao.

Volume Intensity Weighted Tone (Xi – Zhao) in People’s Daily

Source: Vemuri, Johnson, Sullivan, GDELT

The fact is that tones in Chinese press for senior leaders differ significantly over time.

The question is whether this maps to the senior leader’s relative standing and whether this has implications for future leadership transitions.

But how does the story end?

The analysis in this paper is designed to measure facts and suggest questions. Further work is required for answers to be definitively provided to these suggested questions. Additional research is suggested across a range of case studies to understand the drivers and impact of tone differentials, or different stories being told, to various internal and external audiences. These tone differentials hold promise to better illustrate diversionary efforts vs. efforts designed to change facts on the ground, as well as highlight when divergence signals rising risk of action.

Bibliography

Abdelal, R., Herrera, Y. M., Johnston, A. I., & McDermott, R. (2006). Identity as a Variable. Perspectives on Politics, 4(4), 695–711. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592706060440

Baggot, E. (2022). Three Essays on U.S. – China Relations. Retrieved September 6, 2022, from https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/33493282

Betz, D. (2008). The virtual dimension of contemporary insurgency and counterinsurgency. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 19(4), 510–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592310802462273

Betz, D. J., & Phillips, V. (2017). Putting the Strategy back into Strategic Communications. Defence Strategic Communications, 3(3), 41–70.

Blanchette, J. (n.d.). Reading the People’s Daily (July 2021). https://open.spotify.com/episode/0UWYyk0jyAF8nvhEklBcwr?si=w9zO4wBVTgS4aIWHFRnbxQ&dl_branch=1

Brady, A.-M. (2015). CHINA’S FOREIGN PROPAGANDA MACHINE. Journal of Democracy, 26(4), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0056

Callahan, W. A. (2006). History, identity, and security: Producing and consuming nationalism in China. Critical Asian Studies, 38(2), 179–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672710600671087

Chapman, T. L. (2009). Audience Beliefs and International Organization Legitimacy. International Organization, 63(4), 733–764. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818309990154

Chu, Y. (2013). Sources of Regime Legitimacy and the Debate over the Chinese Model. China Review (Hong Kong, China : 1991), 13(1), 1–42.

Chubb, A. (2019). Assessing public opinion’s influence on foreign policy: the case of China’s assertive maritime behavior. Asian Security (Philadelphia, Pa.), 15(2), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2018.1437723

Clare, J., & Danilovic, V. (2010). Multiple Audiences and Reputation Building in International Conflicts. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54(6), 860–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002710372741

Dawes, R. M. (1999). A message from psychologists to economists: mere predictability doesn’t matter like it should (without a good story appended to it). Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 39(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(99)00024-4

Dixit, A. K. (2009). Democracy, Autocracy and Bureaucracy. Journal of Globalization and Development, 1(1), 1-. https://doi.org/10.2202/1948-1837.1010Downs, E. S., & Saunders, P. C. (1998). Legitimacy and the Limits of Nationalism: China and the Diaoyu Islands. International Security, 23(3), 114–146. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539340

Fearon, J. D. (1994). Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes. The American Political Science Review, 88(3), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.2307/2944796

Fearon, J. D. (1997). Signaling Foreign Policy Interests: Tying Hands versus Sinking Costs. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(1), 68–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002797041001004

GDELT-Global_Knowledge_Graph_Codebook-V2.pdf. Retrieved February 19, 2022, from http://data.gdeltproject.org/documentation/GDELT-Global_Knowledge_Graph_Codebook-V2.pdf

The GDELT Project. Retrieved February 19, 2022, from https://www.gdeltproject.org/

Geddes, B. (2009). How Autocrats Defend Themselves Against Armed Rivals (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 1451601). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1451601

Jervis, R., Lebow, R. N., & Stein, J. G. (1985). Psychology and Deterrence. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Johnston, A. I. (2017). Is Chinese Nationalism Rising? Evidence from Beijing. International Security, 41(3), 7–43. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00265

Kewalramani, M. (2021). Manoj Kewalramani – Tracking People’s Daily. https://trackingpeoplesdaily.substack.com/people/1886478-manoj-kewalramani

Lebow, R. N. (1981). Between peace and war: the nature of international crisis. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Levy, Jack. (1997). Prospect Theory, Rational Choice, and International Relations. International Studies Quarterly, 41(1), 87–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00034

Lipset, S. M. (1981). Political man: the social bases of politics (Expanded ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nye, J. (2017). Soft power: The origins and political progress of a concept. Palgrave Communications, 3(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.8

Plato. (1888). The Republic of Plato. Macmillan and co. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.FIG:007212196

Machiavelli, N. (2005). The Prince. Bedford /St. Martin’s, ;

Miller, M. C. (2021). Why Nations Rise: Narratives and the Path to Great Power. University Press, Incorporated.

Shi, Y. (2014, November 7). China allows rowdy anti-Japanese protests | Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/world/china-allows-rowdy-anti-japanese-protests

Sullivan, J. (2022). The Nature of Power: A Metcalfe’s Law National Security Strategy. Security Nexus, 23(2022). Retrieved August 15, 2022, from https://apcss.org/nexus_articles/the-nature-of-power-a-metcalfes-law-national-security-strategy/

Sullivan, J., & Batra, R. (2020). Politics by Numbers: Quantifying populism. J.P. Morgan. https://markets.jpmorgan.com/research/PubServlet?forcePdf=1&action=open&doc=GPS-3466291-0&&referrerPortlet=search_publication&referrerPage=publication_page&referrerUrl=https://markets.jpmorgan.com/research/CFP?page=publication_page&publicationId=9002089

Sullivan, J. R. (2022). Grey Zone Tactics as Catalysts for Balancing Coalitions: A Level of Analysis Approach [Masters, Harvard University]. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/37371532

Sun, Y. (2001, November 30). Chinese Public Opinion: Shaping China’s Foreign Policy, or Shaped by It? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/chinese-public-opinion-shaping-chinas-foreign-policy-or-shaped-by-it/

Zhang, P., Shih, V., & Liu, M. (2018). Threats and Political Instability in Authoritarian Regimes: A Dynamic Theoretical Analysis. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3218676

Zhu, H., Ng, G., & Ge, T. (2022). China: A preview to the 20th Party Congress. J.P. Morgan. https://markets.jpmorgan.com/#research.article_page&action=open&doc=GPS-4118179-0

The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the DKI APCSS or the United States Government.

November 2022

Published: November 21, 2022

Category: Perspectives

Volume: 23 - 2022

Author: James R. Sullivan