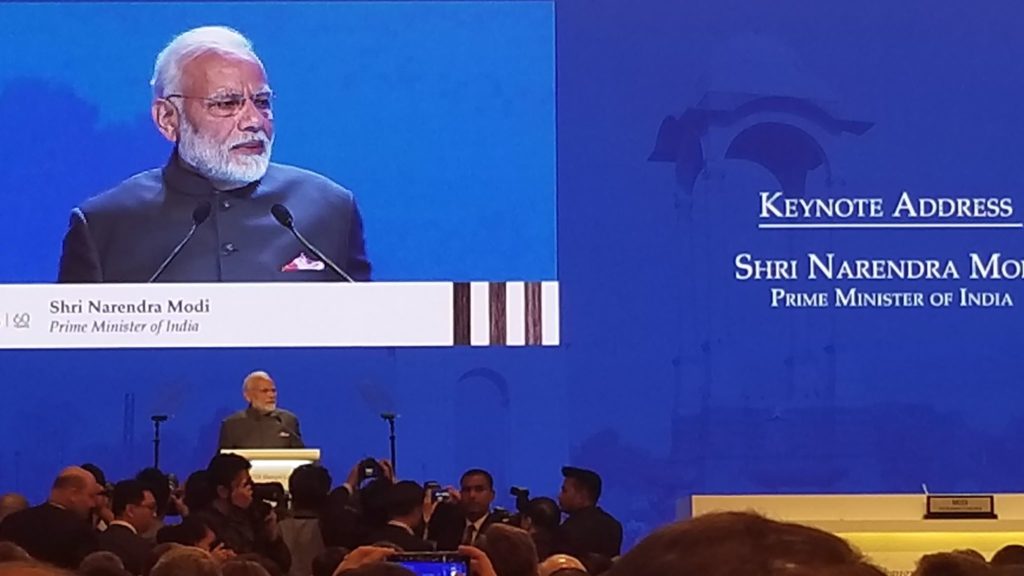

Shri Narenda Modi, Prime Minister of India, speaks at the Shangri-La Dialogue. Photo by K. Nankivell

In Defense of the Rules-Based International Order

Reflections from Shangri-La Dialogue #SLD18

1 – 3 June 2018, Singapore

By Kerry Lynn Nankivell, DKI APCSS Professor

Defense of the Rules-Based International Order (RBIO) is shaping up to be the leitmotif of 2018. At the annual Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD), the region’s premier Track 1.5 defense and security dialogue, preoccupation with adherence to rules, laws and norms, and the regional order to which they give rise, was a theme that appeared in nearly every official speech. From the opening keynote compellingly delivered by India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis’ opening remarks and Singapore Minister of Defence Ng’s closing thoughts, it seemed clear that the region’s residents – large and small – are preoccupied with increasing uncertainty about the stability of the long-held rules of the road that have underpinned regional prosperity and stability for decades.

Profound uncertainty pervades three major regional issues. The first is nuclear non-proliferation and the Korean peninsula. Defense Ministers Song (ROK) and Onodera (Japan) understandably made this issue the theme of their SLD18 remarks, and supported by Ministers from Canada, France, the U.S. and U.K. expressed their commitment to pursue Complete, Verifiable, Irreversible Denuclearization (CVID) through negotiations with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Nearly all speakers acknowledged the failures of past negotiations, in which agreements were struck even as parties neglected to implement the provisions to which they had agreed. Moreover, international instruments including the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), as well as three United Nations Security Council Resolutions since 2017 have failed to deter North Korea’s steady march to nuclear capability. In fact, decades of diplomatic frustrations seem only to have led to the undeniable nuclearization of the Korean peninsula (the Kim regime has successfully undertaken three nuclear tests and many more missile tests since 2015). It is little wonder that this year’s security summit included a palpable sense of cynicism about the power of treaties, negotiations or even face-to-face diplomacy to bind parties to the basic rules of good conduct. With few consequences for bad behavior, but even fewer alternatives to negotiation, many of us will do as French Minister Parly recommends: endure the cold shower of reality while two armies of plumbers on either side of the Pacific work furiously to get the heat back on.

The international rules-based order is also under visible strain in the global maritime commons, but particularly in the South China Sea. Since April 2018, China has deployed anti-ship missiles to the disputed Spratly Islands, landed a strategic bomber on Woody Island in the disputed Paracel Islands, and conducted a live-fire exercise inside the waters of its infamous nine-dashed line claim, despite the fact that it was invalidated by an internationally-recognized Arbitral Award ruling in June 2016. Opening the Shangri-La Dialogue, U.S. Secretary of Defense Mattis plainly called out Chinese behavior as a blatant use of military power for the intimidation and coercion of her smaller neighbors. Moreover, he correctly noted that the nine-dashed line “does not exist”, having been evaluated and dismissed in an international legal ruling. Prime Minister Modi adopted a maritime theme for his keynote remarks, and without singling out Chinese behavior, reminded the audience of the importance of international law and respect for dispute resolution mechanisms, as well as the sanctity of sovereignty and territorial integrity to the regional order. Ministers and Chiefs of Defense from Australia, Canada, Japan, Germany, France, U.K. shone a light on Chinese behavior to greater or lesser extents, defending the principle of freedom of navigation as a cornerstone of the international order. But despite the growing unanimity of support for UNCLOS and the rules and norms that it codifies, there is much hesitation and uncertainty about what can be done in the face of determined and repeated violations of the rules by powerful states. U.S. Secretary Mattis averred that “there are consequences” for ignoring the rules, and that China’s recent “disinvitation” to the annual Rim of the Pacific Exercise is only one small one. But questions from the audience and sidebar commentary remains frustratingly stymied on the question of what feasible options are available to those that seek to defend the rules-based order at sea.

Last, and to a much lesser extent, various senior speakers in Singapore expressed doubts about the health of the rules-based order underpinning economic trade and investment. While one U.S. Senator highlighted “predatory economics” that offer a “hand out, not a hand up”, India’s Prime Minister Modi warned of increasing protectionism and nations “plagued under impossible debt”. Speaking more plainly than most, Singapore’s Minister Ng unapologetically equated the White House’s unilateral imposition of large-scale steel and aluminum tariffs to Chinese unilateral military action in the South China Sea. Softening support for the existing international agreements on free trade was also called out as a troubling trend by those Ministers coping with the day-to-day reality of terrorism and returning fighters, including Ministers Lorenzana (Philippines), Ryamizard (Indonesia) and Attiyah (Oman). Oman’s Dr. Attiyah persuasively noted that terrorism has “no root cause”, but also stressed that comprehensive investment and development needs to be a strong thread in any successful, multi-layered counter-terrorism policy. This is a difficult reality at a time when domestic publics in many countries seem weary of globalization and its socio-cultural effects, and suspicious that international trade has benefited some more than others. As in the other two issue areas, the weakened confidence in established rules, norms and laws of international behavior leaves policy makers with few options in charting the way ahead. Dissatisfied with the rule set of the past, the world’s leaders are standing in an unfamiliar transition zone without a clear vision of what lies ahead.

Despite much uncertainty, this year’s Shangri La Dialogue did underscore a nearly-unanimous support for the regional architecture of security cooperation, of which the SLD is an integral part. Nearly every speaker reiterated her or his recognition of ASEAN’s centrality to the regional security order, alongside an alphabet soup of mechanisms, forums, regularized exercises and activities. Continued engagement via these and other, less formal mechanisms, including education and training programs like those offered by DKI APCSS, will become increasingly important as we seek to shore up the international rules-based order. Only dialogue and mutual understanding will help us to build Modi’s “free, open and inclusive” regional order. Secretary Mattis stated in his remarks that “years from now, we will be judged on whether or not we successfully integrated new powers to our existing order.” If we are to meet that challenge, we’ll need to redouble our efforts to understand and engage with one another. “We will sail forth”, as French Minister Parly declared, not in spite of uncertainty but because our willingness to move forward together, cautious but optimistic, committed to cooperative outcomes, is the best foundation for a more stable Indo-Pacific.

Background

Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis meets with Vietnam’s Minister of Defense Ngo Xuan Lich during the Shangri-La Dialogue. US Navy Photo

Every year the world converges on Singapore. The Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD) was created in 2002 by London’s IISS (double-I, double-S0, and remains the premier security event in Asia. Officially a Track 1.5 dialogue, over 17 years of its history it has become a leading forum for sitting heads of state and ministers of defense to present their views and engage with their peers on issues of interest. In addition to the one-and-a-half day program of plenary presentations and thematic panels, the SLD also facilitates private bilateral meetings for ministers and senior government officials. This year’s event, held from 1-3 June 2018, was a resounding success, convening 561 delegates, over 300 of which were official representatives of 51 nations, and over 1000 badged participants. This year’s conference hosted a record number of Ministers of Defense, Chiefs of Defense and National Security Advisors. In addition, there were 537 members of the press working on behalf of 150 media organizations. The United States was represented by Secretary of Defense James Mattis, Secretary of Navy Richard Spencer, four members of Congress, and three U.S. Senators. U.S. Military delegates included NATO Deputy Secretary-General Rose Gotemoeller, Commander U.S. INDOPACOM, ADM Philip Davidson, and Commander U.S. Logistics Group Western Pacific Task Force 73 RADM Donald Gabrielson. By the time the conference drew to a close on June 3rd, delegates had heard 37 presentations from including 13 from Ministers of Defense. The internet had logged more than 13 million impressions of #SLD18.

In international diplomacy, sometimes presence is used as a substitute for substance. The mere act of collecting so many empowered individuals – those most directly responsible for security and defense in the Indo-Pacific – is an important feat. Emerging from their domestic contexts to engage in a few hours of face-to-face engagement is tremendously important to building shared understandings of one another’s priorities and strategic intent. But in this regard, SLD is not your conventional diplomatic event. Hosted by IISS, a global think-tank based in London with a regional office in Singapore, the SLD is also the site of much official government business. This year, 961 bilateral meetings were held between government officials in attendance, and at least one Minister, Eng Hen Ng from Singapore, confirmed that his government signed two strategic cooperation agreements with foreign counterparts during the Summit. In its 17th year, the Shangri La Dialogue has undoubtedly established itself as an integral part of Asia’s complex regional security architecture.

Related links:

Kerry Lynn Nankivell is a professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security studies. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of DKI APCSS, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Leave A Comment