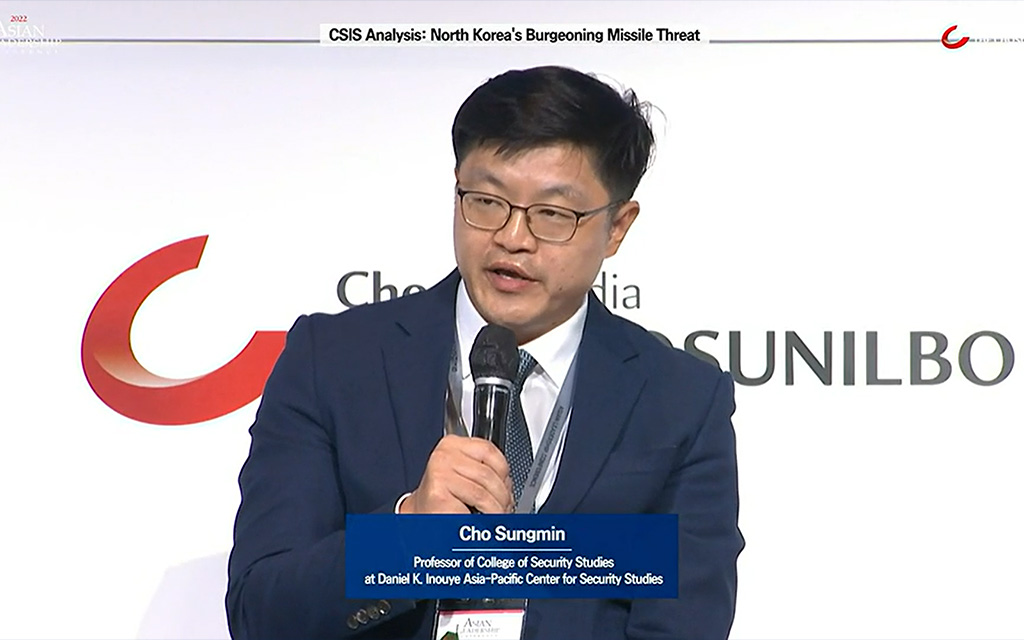

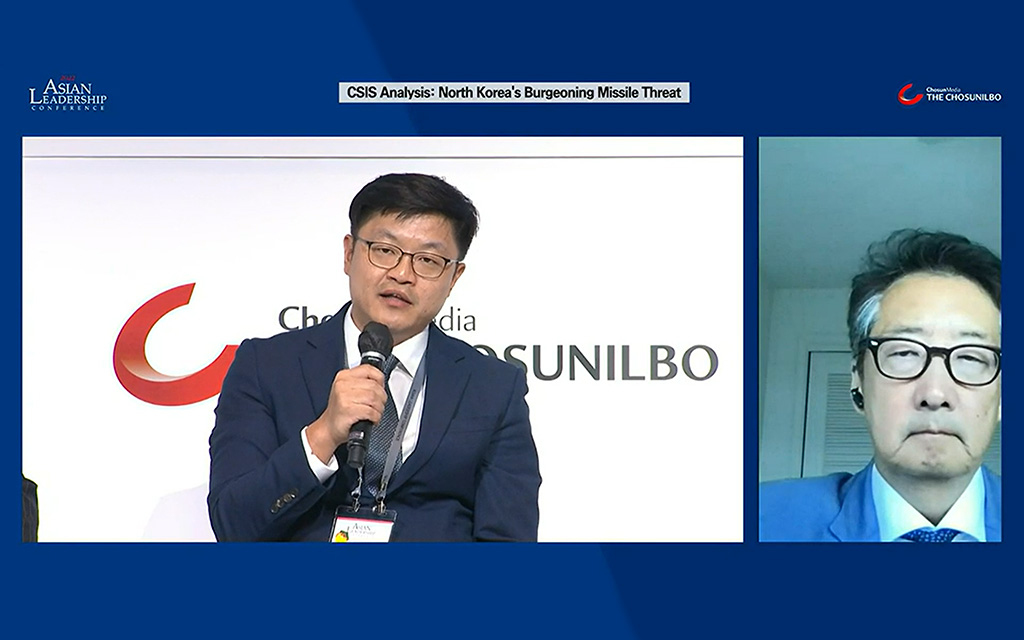

On July 14, DKI APCSS professor Dr. Sungmin Cho joined a panel of experts to discuss North Korea’s most recent nuclear tests and the effects of the Russia-Ukraine war. In his remarks Dr. Cho presented his analyses on (1) the Chinese view of North Korea’s military provocations in 2022, (2) the impact of the Russia-Ukraine war on the Korean Peninsula, and (3) the possibility of North Korea’s 7th nuclear test.

The session included panelists Dr. Victor Cha, Senior Vice President for Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Mr. Ankit Panda, Senior Fellow of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Markus Garlauskas, nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, and Dr. Duyeon Kim, Adjunct Senior Fellow at Center for a New American Security. Michelle Lee, Tokyo Bureau Chief for the Washington Post, moderated the discussion.

The Asian Leadership Conference (ALC) is Korea’s premier international conference. The Chosunilbo, the largest and most trusted media institution in Korea, hosts the conference to provide a platform for global leaders to gather and discuss the most pressing issues facing the world. Key 2022 speakers included former U.S. First Lady Michelle Obama, economist Jeffrey Sachs, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, and former U.S. Vice President Mike Pence.

Moderator: How do you assess the state of the relationship with North Korea and China? How about North Korea’s relationship with Russia? In what ways are the two countries helpful for North Korea’s development of its missile program?

Dr. Cho: Let me first talk about China’s cost-benefit calculus regarding NK’s missile tests in 2022. First, China benefits from North Korea’s military provocations to distract the US and its allies’ resources from the Taiwan Strait. As Dr. Ely Ratner, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs, commented in December 2021, the peace and stability of the Taiwan Strait remains one of top priorities for the US defense policy in East Asia. The US strategy is to gather support from the allies like Japan, Australia and South Korea. Then, logically speaking, China’s counterstrategy should be to prevent the US allies from getting involved in Taiwan contingency. North Korea’s military provocations helps China to pin down the US Forces Korea, Seoul and Tokyo’s attention on the Korean Peninsula.

Second, at the same time, China worries about the improvement of defense cooperation among the US, Japan and South Korea. China’s biggest fear is that South Korea and Japan develop their own nuclear weapons as a result of North Korea’s nuclear development. There is no doubt that nuclear arming of South Korea and Japan would deteriorate China’s security environment in the long run.

In short, China can benefit from North Korea’s missile tests, but worries about the costs from its nuclear test. That is why China vetoed the U.N. sanctions over North Korea’s missile tests this year, but China’s envoy to U.N. clarified, on June 9, that Beijing clearly opposed North Korea’s nuclear test. China can tolerate North Korea’s provocations at the operational level, but opposes at the strategic level.

Let me add a little bit about China-Russia’s military operations in the vicinity of the Korean Peninsula. In July 2019, China and Russia conducted its first ever long-range combined air patrol near the Korean Peninsula. They flew military aircrafts over the areas of territorial dispute between South Korea and Japan, effectively exploiting the spat between the two countries. In November 2021, China and Russian military aircrafts entered South Korea’s air identification zone (KADIZ) without prior notice. On March 24, 2022, they did it again just hours before North Korea test-fired long-range missile. It is remarkable to me that while we worry if China provides military support for Russia in Ukraine, it is actually Russia that provides military support for China in East Asia. It tells me that Russia is not distracted and maintains a military presence in East Asia. It sends a strong signal to Kim Jong-un that he has a robust grouping of allies to rely on when he needs.

Moderator: What is the impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on the security perception of South Korea and North Korea?

Dr. Cho: The war in Ukraine has deepened South Korea’s own security dilemma between China and the United States. I can summarize South Korean views of the war in Ukraine into two arguments. Some analysts, mostly from the progressive side, argue that Putin decided to invade Ukraine because of NATO’s expansion to the Russian border. The lesson for South Korea is that Seoul should be careful about Beijing’s threat perception. South Korea should maintain a balanced approach in the middle of US-China strategic competition. Other analysts from the conservative side argue that Putin invaded Ukraine precisely because he was convinced of the lack of US resolve to intervene. The lesson that they draw from the war in Ukraine is the opposite: Seoul should double down on strengthening the US-South Korea alliance to ensure U.S. resolve to defend South Korea.

What this debate in South Korea implies is that, if Ukraine falls or compromises, China and Russia can propagate the narrative that the U.S. is not a reliable ally and Seoul would better not to antagonize China, otherwise it may meet the same fate as Ukraine. This is why South Korea, along with other US allies and partners in East Asia, also has a stake in the changing situation in Ukraine. It impacts the narratives about US credibility and security perceptions in East Asia as well.

Moderator: The U.N. Security Council can’t even jointly respond to a ballistic missile test. What consequences would DPRK face in the aftermath of a nuclear test?

Dr. Cho: I think three events will happen subsequently.

First, China and Russia will not endorse the UN sanctions. Beijing perceives that more sanction is no longer a viable solution for North Korea problems, and Russia itself has been under the economic sanctions. They disagree with the Western approach to impose more sanctions against North Korea.

Second, whether the UN Security Council passes a resolution or not, Seoul and Tokyo would not have much expectations that sanctions can change North Korea’s behaviors. Since 2006, the UN Security Council issued nine resolutions to sanction North Korea but they could not stop the country from conducting six nuclear tests. The 7th nuclear test will most likely to spark a heated debate about the option of nuclear armament in South Korea and Japan

Third, China will then threaten to retaliate South Korea economically or militarily. Nuclear arming of South Korea and Japan has been China’s biggest fear when it comes to North Korea provocations. Beijing interpreted the THAAD deployment to South Korea as a US conspiracy to contain China. There is no doubt China will interpret South Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapon in the same way and China take actions to stop South Korea from doing it.

But it should not be forgotten that it is not only North Korea, but China also has recently strengthened its nuclear capabilities and Russia threatened to use nuclear weapons as well. Therefore, it is not irrational for Seoul and Tokyo to consider nuclear armament from the logic of balance of power.

Dr. Sungmin Cho is a professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies. The views expressed in this article are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of DKI APCSS, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Leave A Comment