by Prof. Jessica Ear

Professor Jessica Ear shares her experiences with Fellows attending the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. Photo by William R. Goodwin.

Associate Professor Jessica Ear presented a lecture at the Japan National Defense Academy located in Yokosuka, Japan on January 7, 2014 on the future of U.S. humanitarian assistance and disaster response (HADR) in Asia Pacific. A summary of her lecture follows.

Following the aftermath of the March 3, 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster that devastated Japan, the U.S. military and the Japan Self-Defense Force conducted a large-scale, joint-disaster mission dubbed, Operation Tomodachi[1]. Although there were lessons to be learned from the joint experience, Operation Tomodachi was in large part, heralded to be a successful example of how two militaries demonstrated strength and determination to coordinate and cooperate during a traumatic humanitarian crisis.

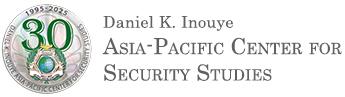

Humanitarian assistance and disaster response such as Operation Tomodachi, will continue to be a priority for both the Asia Pacific and for the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). This is because Asia Pacific is the most disaster prone region in the world. Each year the region bears the highest number of disaster occurrences as well as consistent reported deaths. In 2012, the Asia Pacific accounted for 40.7% of global disasters and 64.5% of disaster mortality.[2] Disaster impacts are also increasing as this region witness greater population growth and thus increased vulnerabilities, mostly in dense urban centers located in low to mid-income countries. Adding rapid economic and infrastructure development to the fast growth in this geographically volatile region leaves a vulnerable population exposed to annual hazards that will result in an increased, more compounded disaster risk.

Infographic @UNISDR (www.unisdr.org)

U.S. military response to past, present and future disaster devastation in the region is possible due to U.S. legal authorities that allow the DoD to provide humanitarian support through a civilian-led, inter-agency process. With its unique capabilities and through lessons learned from past humanitarian missions, the military is becoming more adept in supporting large-scale disaster relief. This adeptness in HADR responses however, while appreciated, has potential to eclipse other civilian actors and may even erode the motivation for others to build self-capacity. Therefore it is important for DoD to take a strategic approach in creating regional capacity to better respond and manage disasters. As the U.S. “rebalances” to Asia Pacific under a tighter fiscal climate, the future of DoD’s) humanitarian assistance in disaster relief (HADR) missions will require a more targeted emphasis on value-adding partnerships and greater investments in education and training with an aim to build risk reduction capabilities and, more importantly, empower nations to leverage relationships in order to meet future regional HADR needs.

DoD’s capability to deploy HADR assets originated with the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 by which the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was designated a key administer of foreign, non-military humanitarian activities. Other actors such as the DoD are to support USAID. Subsequent to the Act, DoD Directive 5100.46 expanded foreign assistance through updated DoD policy and component responsibilities. 5100.46 allowed military commanders immediate or near a disaster, to take prompt action for up to 72 hours without Department of State (DoS) approval. Since then, five other U.S Code Title 10 authorities further legitimize and expand military engagements in foreign disaster assistance. With each new USC authority, the role and capacity of the military to act in HADR is stretched to with regard to funding, supplies, and transport;[3] all capabilities that make the U.S. military affective in large responses today.

When a disaster occurs in the region, and before the military can assist, the U.S. interagency process requires the U.S. Ambassador in the affected country to send a disaster declaration cable with three criteria. First, the cable must confirm that the affect state requested or are willing to accept assistance from the United States. Second, the cable must state that the disaster is beyond the ability for the affected state to respond. Lastly, the cable must justify that response is in the interest of the U.S.

The cable from the U.S. Embassy in the affected nation triggers an inter-agency vetting and approval process that starts with the DoS coordinating with the U.S. lead agency, USAID/OFDA, to send a Disaster Assessment Response Team (DART) to the location. If deemed necessary, DoS and USAID/OFDA will request DoD support via an Executive Secretary memo. That request then flows from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff onward to the Combatant Commander in the form of an Executive Order for action. The Combatant Commander then has the authority to deploy appropriate assets, often times a Joint Task Force, to the affected region. The communication between departments can happen very quickly with “short cut” coordination between all U.S. interagency stakeholders in times of tremendous need. However the process is to ensure that relevant decision-makers assess and vet disaster assistance offers and requests to better determine the need for U.S. military support.[4]

The U.S. approval process to determine need for military assets is in congruence with the international Guidelines on the Use of Foreign Military Civilian Defense Assets in Disaster Relief, also known as the “Oslo Guidelines.” The Oslo Guidelines are explicit in stating that military assets “should be requested only where there is no comparable civilian alternative.” In other words, HADR missions are to use civilian capacities where available and reserve military assets to be used as a last resort.[5] Proponents to limiting use of military support argues that it better separates war-fighting from humanitarian work, a space buffer most humanitarians deemed necessary to convey neutrality and therefore increases access to help affected populations. Additionally, designating military assets as a last resort places first demand on affected host nation and humanitarian organizations to act, and in doing so can build up future disaster response capacities and efficiencies through experience.

Affected host nations are also sensitive to foreign military assistance without their request or confirmed consent. Besides potentially violating international laws of sovereignty, affected nations are attuned to perceptions of incompetence and their potential loss of face in the eyes of the people and the world should the U.S. arrive to help without their request or permission. More and more often though, the scale of disasters in the Asia Pacific creates great human and economic loss, frequently overwhelming the affected nation. It is then that U.S. military assistance is widely requested or offered immediately after disaster impact. For the DoD, having military involvement in HADR means the opportunity to help humanity, to affirm relationships, create global goodwill and practice knowledge and skills. This occurred most prolifically during the Asian Tsunami (2004), Operation Tomodachi in Japan (2001) and the recent response to cyclone Haiyan in the Philippines (2013). Increasing regional disaster frequency indicates a need for such continued military HADR assistance in the future.

U.S. Military support to HADR, although unique in capability and large in presence, are actually few in numbers when compared to the count of reported disasters that hit the region each year. In 2005 for example, there were 500 disasters that affected nations. Out of 500 disasters, the U.S. responded to 79 events and out of those responses, only six occasions involved the military. The other responses were undertaken by other U.S. civilian agencies and actors.[6] Even though the number of U.S. military assistance in HADR operation is limited each year, the U.S. military power to support mega disasters is due to its superior capabilities in the areas of command, control and communications; logistical lift and transport, and ability to provide security to assistance operations.

While civilian actors such as the United Nations have communications and logistics capabilities for HADR, the U.S. military with its technology and fleets of ships, planes and other transport vehicles can deploy at a larger scale, and frequently more rapidly to create ease of access for humanitarian actors and aid delivery in hazard- stricken areas. An example of this efficiency was observed at the Sendai airport. Four days after the tsunami U.S. military personnel, upon a few hours arrival at the scene, helped the Japanese to clear and restore 5,000 feet of runaway to receive its first military aid flight that same afternoon. The airport was open again for commercial flights a few weeks after that.[7] Uniquely, militaries also have the capability over civilian responders to provide force protection and security in disaster affected areas where enemy combatants may be present.

Marines from Combat Logistics Regiment 35, 3rd Marine Logistics Group, III Marine Expeditionary Force, use heavy equipment to help repair damaged areas surrounding the Sendai Airport here March 25. U.S. service members have been assisting the Japanese Government in providing relief in areas affected by the devastating 9.0 magnitude earthquake and subsequent tsunami that struck northern Japan March 11. Photo by Gunnery Sgt. J. L. Wright Jr.

Through its past and recent military humanitarian responses, the U.S government has recognized HADR’s significance in improving force inter-operability, fostering goodwill, enhancing nation to nation relationships, and importance to overall security cooperation. This is evident through evolved U.S. defense strategic guidance and priority shifts that highlight HADR as one of the key areas for regional cooperation. Each HADR mission creates greater understanding of disasters risk concepts and coordinating mechanisms among combatant commands, its components, HADR actors and others involved. HADR missions have incrementally built institutional know-how, improved on interagency, cross-sector and even regional coordination. Yet response coordination can still be more effective and efficient. Complications still persist to hinder HADR missions in areas such as language and culture differences; ease of communication; operational standards and procedures; information access and sharing; resource management; skill and knowledge capacity gaps.

With budgetary cuts and reduction, the DoD will be challenged to prepare for future HADR operations in the region. The Asia Pacific will continue to advance rapidly while Pacific Command is expected to maintain a “ready and capable force,” versatile both in war-fighting and in humanitarian missions. Throughout the evolving security landscape, relationships with allies and key partners will become increasingly critical. DoD can build greater networks and collective capability with allies and partners, to include emerging partners, to contribute and add value to future HADR missions. Empowering partners to share costs and responsibilities to better manage and respond to disaster will better leverage resources, know-how and capacity to save lives and mitigate damage. The larger question is how DoD should do this in a manner that will target and improve on challenges expressed in repeated HADR after action reviews.

One approach is to directly target the core of these repeated HADR challenges: its people. People define risk management and disaster operations by the policies they shape, the decisions they make, and the skills they demonstrate. Knowledge, networks and abilities of HADR leaders can resolve or overcome obstacles in language and culture; communication; operable standards and procedures; information access and sharing; and resource management. Knowledge and skills development of security practitioners from the region (and the U.S.), promotes more effective and efficient disaster risk management and humanitarian assistance because it fosters greater understanding of each other’s values, perspectives and approaches to enhance effectiveness. Joint education and training brings leaders together to break down these barriers. This improved understanding can foster shared interests in inter-operability, efficient resource management and effective institutional governance, all elements crucial to HADR missions.

Education also creates opportunities for networking to achieve long-lasting relationships and promotes the spirit of cooperation in HADR. In the context of mega-disasters and the tremendous human and economic loss to the region each year, joint education and training may be the most sustainable, most cost-effective means of achieving an end. Educating HADR’s present and future leaders mean investing in national capability to self-respond and assist others in disaster crises. Strategically emphasizing joint leader education and training through DoD’s security cooperation programs builds needed expertise, enhances relationships and empowers a cooperative spirit to weather and assist in the region’s future disasters.

[1] Tomodachi is the Japanese word for friend.

[2] Center for Research in the Epidemiology of Disaster, Annual Disaster Statistical Review, 2012. http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ADSR_2012.pdf

[3] 10 U.S.C sections: 401,402,404,2557,2561

[4] : “Department of Defense Support to Foreign Disaster Relief, Handbook for JTF Commanders and Below,” 13 July 2011.

[5] Guidelines on the Use of Foreign Military Civilian Defense Assets in Disaster Relief, UNOCHA, 2007.

[6] “Climate Change: Potential Effects on Demands for US Military Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response,” CNA Analysis & Solution, 2010.

[7] U.S. Department of State, “Reopening of the Sendai Airport,” Teleconference Briefing with Air Force Colonel Robert Thoth, Commander, Joint Force Special Operations Component Joint Support Force-Operation Tomodachi, New York, April 15, 2011. http://fpc.state.gov/161156.htm

-End-

The views expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of APCSS, the U.S. Pacific Command, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Leave A Comment